A few years ago, I attended an art museum with Ania and one of her friends from her hometown. There was friction between the three of us. Ania hadn’t been in much contact with this friend for years at this time, and importantly, had come into her atheism and become involved with me in that gap. Her friend, in turn, was still religious. I earned some of her friend’s future antipathy to me by being a little too insistently flirtatious, which is not a good thing for a perceived cis straight man in a relationship to be toward a woman who is clearly uninterested, but most of it preceded that unfortunate buildup. A lot of it coalesced into a rather unfortunate turn of phrase she used during that art museum trip:

“[S]he’s not one of those atheists, is [s]he?”

One of those, you see. The insufferable logical-positivist, probably-libertarian-and-transhumanist nonbelievers who disavow the importance or value of anything other than cold, hard truth, and therefore see all non-representative art, fiction writing, and other figurative pursuits as a waste of energy that could have gone into science and engineering, the only acceptable livelihoods for the intelligent.

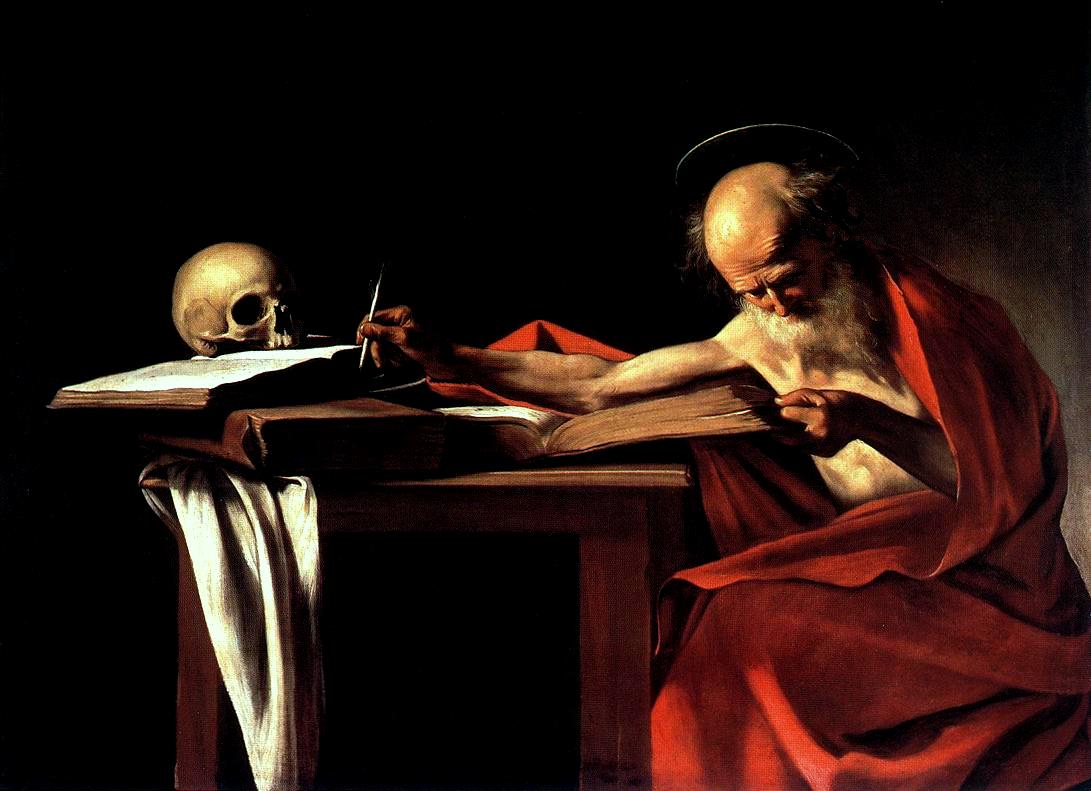

All she needed to hear was that I’m not particularly fond of religious art in the style of Caravaggio (the National Art Gallery’s special exhibit at the time) to suddenly have me pegged as the stereotype Christians like to hurl at atheists: that we’re joyless, soulless automatons incapable of perceiving beauty or joy and who are particularly unable to see any value in religious imagery.In reality, I’m not particularly keen on Caravaggio’s work because I find his reliance on illumination patterns instead of foreground and background to highlight the features of his subjects robs them of context and place and makes it harder for me to relate to the emotions he’s otherwise very, very good at evoking. Emotions are different when they’re felt in a private room, at a secret lookout point, or in a deserted public square at night, and Caravaggio sets this idea aside in favor of a plain black background that tries to be universal and instead fits nowhere, as far as I’m concerned.

I hadn’t thought this out further than “I don’t like the ones with black backgrounds as much as the ones with colorful backgrounds” when I told Ania why I was less enthusiastic about the hall of Caravaggio’s religious scenes, and that’s all she had to defend me from her friend’s presumptions about my relationship with the religious artist. She could, at least, also evoke my appreciation for the ornate interior architecture of ancient churches to force her friend to deal with the fact that I have no overt disdain for religious art simply because it’s religious art, or for art altogether.

It’s an old accusation, that there is something fundamentally inhuman about atheists and other folks who doubt the truth of religion. Whether it’s claims that we eat infants, claims that we’re incapable of basic morality, or claims that our perspective on nigh-universal experiences is so alien as to be incomprehensible to someone who has seen godly light, it’s an important plank of just about every Abrahamic sect and many others that those outside the faith, and in particular those who have no religion at all, are otherworldly grotesqueries beyond mortal understanding or acceptance. It is often pointed even at religious scientists as well, for having the temerity to examine how things actually work and therefore demonstrating a lack of faith. Sometimes they add the idea that consorting with us is a good way to have one’s own “soul” filched away, condemning one to join us. The philosophical elisions and substitutions that make this whole line of reasoning work are quite simple: everything good and pleasant is either a synonym for God or an aspect of God’s influence in the world, as needed, therefore, those who reject the idea of God simultaneously reject all of that and dwell purely in ugliness. The idea that the specific claim that atheists dispute is that a deity is necessary for any of those things is, deliberately, left unacknowledged.

Ania’s friend already thought that about me, as soon as she heard that I was an atheist and, even more so, when she learned that I helped Ania recognize her own atheism. She needed only a convenient scaffold on which to hang the matted web of her prejudice.

This particular accusation, though, has a very important mirror in our culture.

Being atheist is not the only reason why I’ve been accused of being cold, reptilian, heartless, robotic, “overly logical,” and all the other words meant to cull me from humanity for my strangeness. One does not need to find stories of magic men demanding mindless loyalty and laying curses on out-of-season fruit trees implausible to be called a soulless monster—one can also manage by being Jenny McCarthy’s son. Those slurs were and are pointed at me with much more vigor over my being autistic. It is far easier to paint someone as a picture of Lovecraftian malevolence if their manner of communication is so weird and formal that some dark corner of their brain imagines that that’s how a dangerous monster would talk. It is easy to call us immoral when we refuse eye contact “like liars.” It is far easier to see us as barely-human interlopers when group activities others find transcendent—chanting, dancing, shouting at sporting events—are for us instead so overwhelming that we cannot join them at all, when ordinary crowds and conversations make us nervous and awkward, when our need for seemingly inconsequential things to be in very specific configurations vastly outsizes their priority to others.

As the chestnut goes, we’re on the Wrong Planet.

They never manage to see us as more in some ways—more empathetic, more precise, more organized, more sensitive—only less, and ultimately, less than human.

That’s who I have been to too many of them: a simulacrum, that looks like a person but cannot possibly be one, reptilian, robotic, incomprehensible in human terms and therefore to be feared for what it “might be capable of.” Soulless.

A soulless reptile science robot who doesn’t even have the decency to have an ecstatic fit on the floor of the museum in front of all the Caravaggios.

It didn’t hurt as much as it could have to be so casually demonized for being an atheist. It was only…familiar.