Stretching 2.6 million square kilometers and including the countries Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, and Vietnam, the Greater Mekong Region supports significant biodiversity. With its diverse geographic landscape and variety of climactic zones, the area is home to an estimated 20,000 plant species, 1300 species of fish, 1200 bird species, 800 reptile and amphibian species, and 430 species of mammal. Every year, scientists discover new species in this region. In fact, according to the World Wildlife Fund, scientists observed more than 2,000 new species between 1997 and 2014. 90 plants, 23 reptiles, 16 amphibians, 9 fish, and one mammal were discovered in 2014 alone. Among the 139 new species were the soul sucking Dementor Wasp:

The color-changing thorny frog:

The second-longest insect in the world:

The crocodile newt:

and the 10,000th species of reptile:

These new species are part of the amazing biodiversity that is an important part of the lives of the more than 300 million people who call the region home. From the 2.6 million tonnes of fish generated every year by the Mekong to the forests and wetlands that protect towns and cities from mother nature, the Greater Mekong Region provides essential natural resources to nearly 80% of the population of the area. Unfortunately, those same essential resources are in peril:

The Greater Mekong is one of the top five threatened biodiversity hotspots in the world, according to the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Hydropower developments threaten the integrity of the Mekong river; later this year, construction on the Xayaburi Dam in Laos will block the lower Mekong River for the first time, disrupting the free flow of fish and sediment. Communities downstream have vocally protested against Xayaburi and the impending construction of the Don Sahong dam near the border of Cambodia, one of an additional 11 planned mainstream dams that would irrevocably transform the Mekong. Roads and other planned infrastructure developments through the region’s wilderness areas will fragment habitats and provide access to saola and other endangered species. Climate change only increases the pressures on the landscapes through rising temperatures, rising sea levels, and more extreme storms, droughts and floods.

WWF works with governments, businesses, and civil society to create a sustainable future for the Greater Mekong based on healthy, functioning ecosystems. We are spearheading efforts to protect species, helping businesses develop sustainable supply chains, encouraging sustainable forestry and non-timber forest product management, helping communities and governments adapt to climate change, and promoting the sustainable use of freshwater resources.

Scientific exploration has an important role to play in the future of the Mekong region. Fascinating new species like the ones discovered in 2014 can draw more conservation attention to the region, while a thorough understanding of the patterns and distribution of biodiversity can help direct conservation resources to the highest priority areas.

The WWF recognizes that no single solution is sufficient to protect the rich biodiversity of the Greater Mekong Region. Habitat conservation, protection from poachers, smart infrastructure development, maintenance of free-flowing rivers and more-these are important to the future of all the species living in the Mekong (including humans). While there is no single solution to overcoming the threats facing the Greater Mekong Region, there is one important step governments, businesses, and citizens can (and should) take: a commitment to the growth of a green economy:

For the purposes of the Green Economy Initiative, UNEP has developed a working definition of a green economy as one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. In its simplest expression, a green economy can be thought of as one which is low carbon, resource efficient and socially inclusive.

Practically speaking, a green economy is one whose growth in income and employment is driven by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency, and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services. These investments need to be catalyzed and supported by targeted public expenditure, policy reforms and regulation changes. This development path should maintain, enhance and, where necessary, rebuild natural capital as a critical economic asset and source of public benefits, especially for poor people whose livelihoods and security depend strongly on nature.

The threats facing the Greater Mekong Region are not unique to that area. Thanks to human activities like habitat degradation and destruction, the invasion of non-native species, over-hunting and pollution, species and ecosystems around the world face the threat of destruction. Humans are also responsible for another dire threat to life on this planet: global warming.

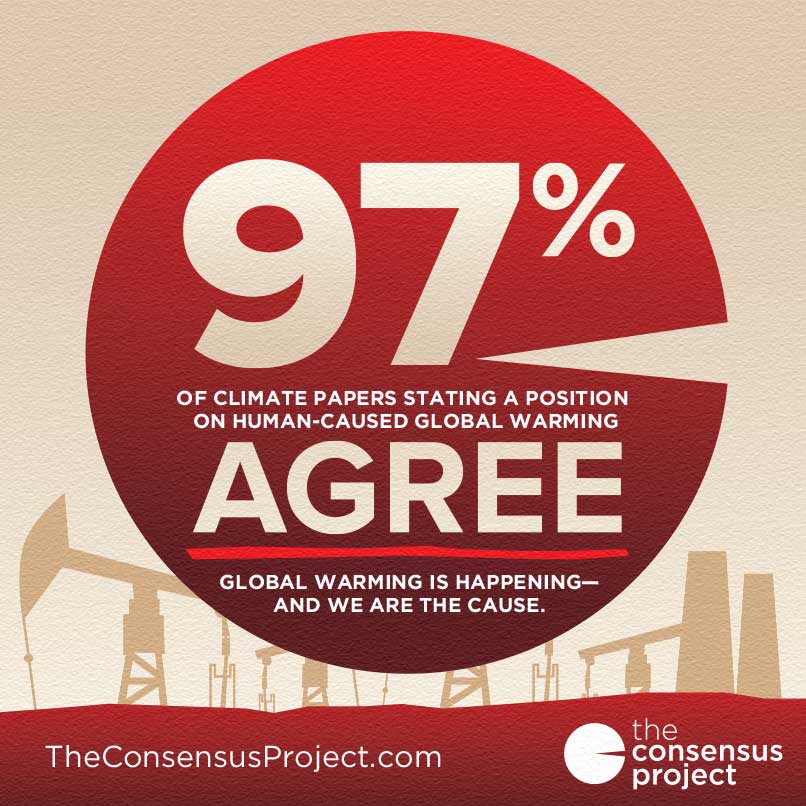

Anthropogenic (human-induced) global warming is a planetary health threat. Left unchecked, global warming will cause changes in the pattern of diseases, food and water insecurity, rising sea levels leading to flooding and migration, increased frequency of extreme weather events and more. It is imperative that governments, businesses, and citizens take steps to address, mitigate, and where possible (if possible), reverse the effects of global warming and other environmental problems caused by human activities. We created these problems. We must take immediate action to prevent them from worsening.

Looking for steps you can take to live a greener life? The Worldwatch Institute has some helpful tips.

Want to support the World Wildlife Fund? They take donations.

For a look at some of the other new species found in the Greater Mekong Region, see here or here.

Want to know more about anthropogenic global warming? Check out the United Nations Environment Programme.