That’s it. I’m doing the big one. The one I’ve been waiting to talk about for a long time.

But, I’m going back on my word — in the last installment of Ethical Gamer, I said I was going to have a bad time. Couldn’t do it. Not sorry.

There are a number of reasons why I couldn’t, but the biggest reason is, there’s a meta-narrative woven into the texture of the game that works in such a way that I can’t bring myself to actually press that reset button.

This game is impossible to discuss from a morality standpoint without heavy, HEAVY spoiling. If you haven’t played it, it’s $10, it’ll take you about 10 hrs to play through to the “good ending”, and longer if you decide you want to also see the “bad ending”. And it is worth literally every penny, I swear to you. If you are a video gamer of at least the SNES era, this is aimed square at you — you are its target audience, and it’s a love letter to everything you love about video games. But the why of it all, I honestly can’t tell you without spoiling the game, so I’ll be doing this below the fold.

Fair warning. Don’t click here if you haven’t played it.

THIS ESPECIALLY MEANS YOU, LUX. Do NOT click! Ah, ah, I saw that! Go finish your Lux Play instead.

A spoiler-free review:

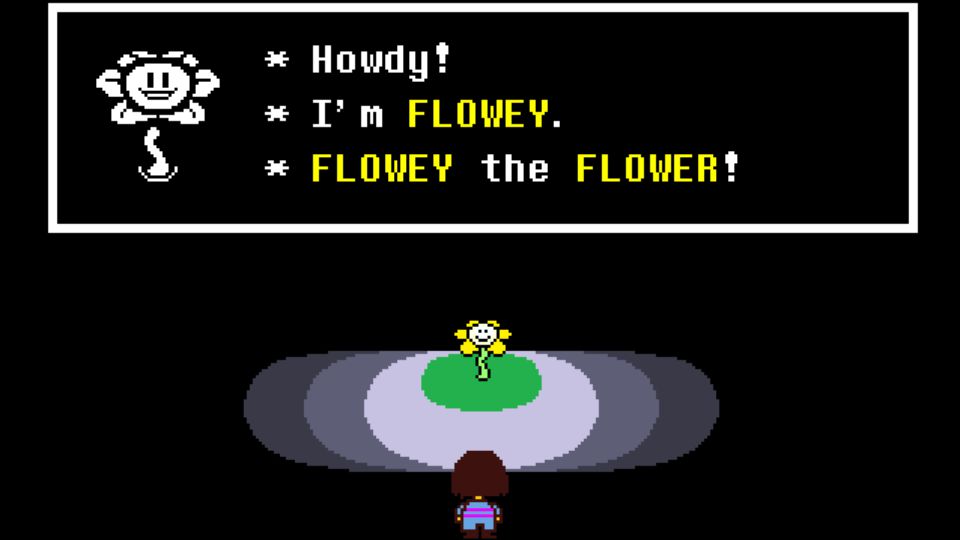

Undertale was, by and large, created by one guy: Toby Fox. He built the majority of the game in Gamemaker Studio, did the majority of the sprites, did all the music, all the plot. A few other people get credit for some parts of the game, like Temmie Chang, or some of the Kickstarter backers who designed certain characters you can encounter. But, the game was a one-man show, backed on a Kickstarter that asked for $5000 but got $50,000 instead. It’s since gone on to sell literal millions of copies, at $10 apiece.

A surface read of the gameplay mechanics would give you little indication why, though. You walk around, fight creatures, dodge attacks in bullet hell, solve very simple puzzles like pushing rocks or flipping switches.

Visually, the game resembles a less-polished SNES-era JRPG, of the sort with tile-based backgrounds, amateurish pixel art, sparing parallax, poor overhead perspective, and even a self-referential joke about how cubes are easier assets to draw than beds. Any programmers using placeholder art in their game tinkerings know that one is a wink and a nudge to those of us who are keenly aware of their strengths and weaknesses who are trying to do just enough to get by, and who hope the strengths overshadow those weaknesses. I feel this one keenly. Graphics are not why you’re here, though.

The music on the other hand, being Toby Fox’s obvious strong suit, is itself worth the price of admission. You can tell he understands both what made a lot of SNES era music great, and how to both use music that is evocative of certain classics like Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy to weave together a cohesive and fitting musical score, and also give us more information, a sort of aural level of feedback, about each of the characters you encounter.

Papyrus’ theme is playful and puzzling, with Bonetrousle reminding me more than a little of Tetris. You never get the sense that the stakes in your fight with him are your life — he’s playing a game, and he wants you to play along, even though losing means he captures you. But that just proves that it was all just a game — your life is never in danger in the fight against Papyrus, and you’ll never see a Game Over screen against him, no matter how poorly you perform against him. Lose several times, and he’ll give up on fighting you altogether, giving you the option to just… skip him. To continue on your journey even though you haven’t earned it.

Toriel’s Heartache grieves that she has to force you to fight, thinking she needs to harden you to face the world, as any good mother might. The music tells you as much about the emotional state of the scene as her attacks and dialogue do, when she loses her resolve and can’t keep aiming them at you when you’ve taken enough damage that you might die on the next round. She WAS resolved to make you make tough decisions, but she couldn’t commit to them herself, even when she was holding your hand literally walking you through puzzles not half a dozen screens back.

And if you’ve been a very naughty little spirit, slaughtering everything in the Underground, Sans — the lazybones who loves his brother and wants to stop the genocidal maniac who killed him — reveals his true power, to the tune of Toby Fox’s long standing signature theme that uniformly means you’re gonna get your shit wrecked: Megalovania. And that music’s instrument samples are not just the peppy chiptune you’ve heard since the beginning — you’re suddenly hearing real electric guitars, drums and a meaty bass line and you know that means shit just got real.

The game’s music doesn’t so much employ leitmotif to tweak the emotions of any particular scene, as it does give you a master class on it. This is clearly Toby Fox’s true forte — not composing specifically, insofar as the composition of most of the songs in the game resemble maybe a little too much some piece of video game nostalgia, but on using leitmotif to directly play a person’s emotions like an instrument unto itself. In fact, I would classify the score as being so integral to the emotional impact of the plot that I would imagine the experience would likely ring hollow without it. This is the first game I’ve found myself revisiting the experience through the music alone, though there’s more than one reason for my not having replayed the game proper.

Those of you who really think you didn’t care about spoilers so much, but are still here because you wanted to simply read the review, now’s your last chance to get out of the pool. Go buy the game. You’ll enjoy it, trust me.

The majority of people playing Undertale, if you’re playing just to get through the main plot and see the ending sequence and don’t care about getting “the perfect ending”, will have had an experience something like this: they will have played through the ruins, maybe fighting a couple of enemies but not necessarily grinding. They will have accepted Toriel at her word that the player must fight her, and cannot show mercy. They will have felt incredibly guilty, and will from that point try to be as pacifist as they can. They will have proceeded through the game with that ethos firmly embedded in their psyches, and they’ll have attempted to avoid at least killing any of the bosses. They’ll have beaten Asgore, and have freaked out at what they see as the “uber boss” in the Eldritch Flowey. But they’ll have achieved the “neutral ending”, being approached afterward by Flowey, who says that maybe it would have been better if you’d not have killed anyone throughout the game. They’ll have escaped the underground via the combination of their own soul and Asgore’s; the pair of souls is enough to allow them to cross the barrier and return home. But everyone in the underground is still trapped.

And he’s about to become possibly the single creepiest antagonist in a video game you’ve ever seen.

But, for some fraction of you, you’ll have realized you did the wrong thing when you killed Toriel. You’ll have reset the game, using the “reset” option on your save file. After you save Toriel at that point, Flowey knows what you did. He calls you on it — he knows you reset the game to save Toriel. And he is unimpressed that you are trying to play by your own rules. He is thoroughly nonplussed by the fact that you have these abilities.

Why is he able to know this? For that matter, why are you able to save your game in the first place? Why do you continue to be able to play this game after being killed? Because, your character has one special ability: determination. It is mentioned at every save point and you think, up until now, that it’s just a cute repeat construction, a little quirk of the way the game was written. And this is a power that, until you entered the underground, only Flowey had. Saving your game, restoring from it, resetting the whole game — that’s not actually just a game mechanic. It exists in the game world as something that another entity — Flowey — can observe and recognize as such. Determination allows you to manipulate time itself.

And during the Eldritch Flowey fight, when he has six human souls in his possession and his powers are exponentially greater than they once were, he is suddenly in full control of time — and he is able to save and load from different save files mid-fight. He abuses save states the way a player might against a particularly tough boss. He saves his state while he starts launching an attack, and if he misses, he’ll load that state and not only thoroughly disorient you (because it all just jumped backward and you can’t react quickly enough to dodge this time), but he’ll save the state after he’s succeeded. The thing that makes Flowey so scary, so thoroughly horrifying as a boss, is not the psychotic imagery he plays on the television he now has for a face, nor the infinitely growing plant limbs he gained, nor the body-horror mouth made out of flesh, teeth and misplaced eyeballs. It’s not the laser-focused attacks that are undodgeable, nor the salvos of bombs that he launches that cover the entire bottom of the playing field, turning it all into an inescapeable “kill zone”. It’s the fact that he’s now in control of everything — of the timeline, of save states, of the game itself. And when he kills you, he laughs at you and then turns off the game, forcing you to re-launch it. He’s taken over the entire game universe to a point where you, as a player, have had every scrap of control stolen from you. Well, not EVERY scrap. I MIGHT get to that soon.

When you beat him, you’ve escaped from the underground, but the monsters left behind are still stuck behind the barrier. Any that survived your neutral run will get an epilogue, e.g. Toriel taking back over as queen of the Underground after Flowey killed Asgore, and Undyne will blame you for his death. But this entire ending is unsatisfying for those of you who look only to be able to say “I beat this game”. That, I’d wager, is by design. Anyone who would be satisfied by this ending is not interested in this game or the narratives enough to know that this can’t possibly be all it has to offer.

If at this point you’ve been scrupulously careful to avoid any death during your run. If you’ve played a pacifist run, the ending is much different. Flowey reveals that you haven’t made friends with every character in the underground, and gives you an opportunity to do so before trying that last fight again. This unlocks Undyne asking you to deliver what amounts to a love letter to Alphys, which in turn unlocks an extra dungeon called True Lab — an underground facility full of body-horror amalgam creatures that turn out to be the result of Alphys having experimented heavily with Determination in an effort to use it to cure dying monsters. You come to learn that Toriel and Asgore had a son, Asriel, who befriended a previous fallen child. You learn that that child poisoned themselves in an effort to give up their soul to Asriel, because the barrier could be crossed by one human and one monster soul in concert. Their plan was to cross the barrier, obtain several human souls on the other side, and then break the barrier themselves.

But Asriel wanted to lay his friend, the fallen human, to rest in his village. The villagers saw the monster and attacked. Asriel couldn’t fight back — he kill anyone, and allowed himself to be attacked and grievously injured by the humans in the village. He returned to the underground and died on his favorite patch of flowers — scattering the monster’s dust and very likely the first fallen human’s soul onto those flowers. It turns out that Alphys had performed Determination experiments on those flowers, creating Flowey. When the new human enters the underground, they somehow get some fragment of Chara — the first human — as a tag-along when they land on the same pile of flowers.

The change in the timeline that Flowey creates to allow a pacifist player to gain Alphys’ friendship turns out to be a Xanatos Gambit though — he wants you to befriend everyone so he can get them all in one place, steal every single monster’s soul, steal all the human souls, and restore his true form of Asriel Dreemur. He’ll then use that power to keep you — the accidental avatar of his best friend, Chara — with him forever in the underground, to play with him forever, to never have your happy ending and never escape.

Flowey had determination, but no soul. He lived in the underground and befriended everyone, but that was unsatisfying. He reset the timeline, and began killing everyone, resetting the timeline over and over. He started seeing everyone in the underground as simple lines of dialogue — as flat objects that responded the same way to the same stimulus every time. Just like a video game. Only the scripted dialogues would come out; it is possible to see everything in a finite dataset programmed by a programmer who, no matter how determined they are to create an infinitely branching narrative, can only provide so many choices in the game as a whole.

Then the character — I should say Frisk, because it turns out that you aren’t naming that character, but the FIRST fallen human, during the title screen — fell into the underground. This was novel to Flowey. You were a newcomer, a new variable. When you appeared, everything was thrown out the window. Who knows how many times the timeline had been reset before you arrived?

But when you arrived, the underground was full of creatures, so Flowey must have recently reset the game. He tries to kill you immediately and take your soul, because you’re new to the underground, and you’re a human, and he knows how the game works. When he failed to kill you, he tried to reset the game again, and failed that too. Your presence as a creature with more determination than him effectively gave you enough power to “stay determined”, to stay in control of the timeline whatever happens. You are — as the player character — a god in this game. As long as you, the player, are determined to keep playing the game, the timeline of the game is in your control.

Such is the case in all games. But this takes the actual game mechanics and weaves it into the game universe in a blatant fourth-wall breaking manner, in a way that it tells you explicitly that you, the player, have more control over the game universe than any entity within it. No matter how true that is in the context of any other game, it seems more immediate and more relevant in Undertale. And when these facts are revealed to you through the true pacifist endgame, you might decide that it’s time to see what the game world is like if you kill everyone.

This is something you can’t trigger accidentally, really. There are very specific conditions to performing a genocide run. You have to grind in every area until when you get a random encounter, instead of fighting a monster, you get a note saying “but no one came.” You have to intend to murder everyone to get this run. You have to be more than passively neutral, trying to get from point A to point B — you have to hunt and destroy. Imagine for a moment playing Super Mario Bros this way — hunting down every turtle and making sure it ended up in a pit, squashing every goomba, using fireballs on every plant. Imagine thinking that if you’re to be a completionist in a game like that, that you’d have to play it that way, intentionally retrying the level if you happen to miss a single monster. As though the meaningless point tally was anything other than a metric of your sadism. That’s what you have to be in Undertale to get the worst ending. (Though, an argument could be made that the actual worst ending is when you try to play pacifist after having genocided the underground… because you did it just to get the now-soulless Frisk, fully possessed by Chara, out into the world to start his rampage there.)

By the time you get to Undyne, you view little children as “free EXP”. She turns out to be the True Hero, and she turns out to have quite a bit of determination of her own. When you try to kill her, her determination is enough to pull herself together and reveal her true power. And she’s a tougher boss than anything you’ll have faced in the pacifist run of the game. Killing her is no mean feat.

When you get to Mettaton, you have to attack with precision to do maximum damage — if you fail to do so, Mettaton comments that you pulled your punch, that you didn’t have it in you to be excessively cruel. At that point, you revert to a neutral run, and all your hard work of going on a murderous rampage will be thrown out the window.

If you make it through everything else in the game, you’ll come to learn that Sans is not “the weakest enemy”. He can do only 1 damage per attack, according to the game’s descriptive text. But it turns out that’s 1 damage per game clock tick. He’s only got 1 defense, so you should be able to one-hit kill him easily enough, even if you were a low level (which if you face him, you’re decidedly not) — but he can dodge everything you throw at him, because unlike other characters in this world who patiently wait their turn to attack you, he knows the game actually allows him to move at this stage. You’re affected by a status effect called KR, which some people suggest stands for “Karmic Retribution”, which means all the damage he does per clock tick actually affects you as a sort of “poison” — he’s applying his hits to your status bar over time, as part of how he can get away with doing “only” one damage. Later in the fight, he starts throwing attacks at your GUI, so that if your soul heart cursor is on a GUI element with an attack on it, you take damage during your own turn. Sans as a character has a thorough understanding of the rules of the game world and subverts every single one of them to his advantage. He is cunning, he is canny, and he is there to wreck your shit, because you’ve been to this point an absolute monster and you’re probably aiming to kill everyone in the human world as well. And he’ll use every part of the game universe and mechanics and even your expectations as a player that he can to stop you.

And, what’s more, he is keenly aware of the temporal shenanigans that your presence signals. He knows about the timelines shifting and stopping when you reset. He knows that every time you’re killed, the timeline resets so that you can make it the next time around. He doesn’t know everything about the game universe or the other timelines, but he’s seen enough temporal shenanigans to be able to sense that he’s “killed you thrice — what comes after thrice? Let’s find out.”

He’s one of the only characters in the game, along with Flowey, to be able to recognize without being prompted that you’ve been there before. Sure, you might be able to tell Asgore that he’s killed you once before, at which point he’ll sadly acknowledge that this is probably the case. But Sans can tell if you’d experienced his joy buzzer intro immediately after the ruins and then reloaded your game to before that point. He, on a pacifist run, recognizes when you’re just jamming through the dialogue at the end of the pacifist run because you’d seen it before. He might even grant you access to his room, and more insight into his character and a giant game secret, if you keep resetting and listening to this speech over and over and thus prove to him you’re a time traveler. Why is Sans able to do this? I have some theories. If you’re interested, find me at some conference and we can discuss over beers.

Even in a pacifist run, Sans has “shortcuts” he uses to go the wrong way on-screen to get to places — he goes right, off screen and toward Hotland, to go back to Grillbys which was actually many screens to the left. During the Flowey betrayal sequence at the end of the true pacifist run, he disappears offscreen on the bottom in order to wrap around to the top where everyone else is. During the fight in genocide, he can jump you and himself into the middle of various sequences of attacks rapidly, not allowing you time to recover and react appropriately, depending on disorientation from having been “jumped” to win the fight. And, tellingly, he’s caused Flowey “more than his fair share of resets” before you came into the picture. Flowey knows enough to avoid this guy, because he — despite pretensions at being the laziest, weakest monster in the underground — is easily the most powerful single creature there.

How’d he get so powerful? Again, ask me over beers. I’m spoiling everything else in this game, but the game’s Big Secret is too big and too nebulous to be anything other than fan-theory speculation. I’m spoiling you only on those things that are directly woven into the game by Toby Fox, who has proven that along with making you care for characters, he can create a deep and layered story with so many moments of awesome, so many giant and shattering reveals, that you can’t believe that through until the end of your neutral run it all seemed very quiet and small and two-dimensional and reliant on skeleton puns and literal rimshots. That you had no idea all of this incredible world-building existed in the story through until the end of your True Pacifist run almost makes you regret playing it all. It was such a simple and unassuming RPG that you probably thought “oh, this is nice, it’s such a simple and unassuming RPG, like those of my childhood”. Then you realize there’s a mature, multidimensional and epic plot underneath it all. And you find yourself needing to explore all of it — every single aspect of this game universe.

But there’s another facet of this game that means it’s a one-way trip for many of us. While everything that happens after the true pacifist (and significantly more satisfying) true ending to Undertale, happens off-screen, if you load up the game again Flowey appears to remind you that Frisk and all the monsters who’d escaped from the underground and are integrating into human society are still subject to one singular and terrible monster — you, the player. If you choose to reset the game, you’ve ripped everyone out of their timelines and have brought everyone back into the underground. Flowey — uncharacteristically, perhaps, though at this point he’s got the memories of Asriel’s true ending, maybe sans the soul that might mean he cares about others any more — implores you to let Frisk have their happy ending. If you reset at this point, you’re destroying that new life, which you’re assured exists even though you can’t see it happening.

If you reset the game so YOU can experience it all again, what about the other characters in the underground? If you’ve accepted the conceit that saving and loading and resetting the game is timeline manipulation, and if you’ve accepted the conceit that each of these characters is deserving of a happy ending, and you’ve taken pains to achieve that happy ending for everyone, what kind of monster are you if you rip them all out of that happiness in order for YOU to experience their companionship again?

Obviously, this is just a video game. These are not real creatures with real lives to consider.

But it’s a video game that’s proven itself more than capable of serving us gamers a love letter, providing us with real moral choices, and encouraging us to buy into the conceits of the game enough that for most people, playing a genocide run is so thoroughly unpalatable to them that they truly feel they’re hurting real people. It has convinced us to buy into the idea that each of these characters is a fully realized person, and that your life is enriched by their presence. It is a thoroughly pro-social game.

Some people hate Undertale explicitly because it makes them feel bad about doing what comes naturally to them, doing what other video games have trained them to do. It tells them that the good feeling, the positive reinforcement of numbers increasing, as a result of their actions within the context of any other video game, implies that they’re being sociopathic — that they’re being selfish and hurting others for brief and temporary hits of endorphins. It damns them for how they play other games by implication. It demands that they consider the life that they destroyed when they bopped that goomba on the head. Many gamers — especially those who scream about “ethics in games journalism” — would rather video games not make you ask big questions about morality, nor promote pro-social behaviour. They’d rather games never become art, that social critique be off limits (unless said social critique agrees with them). They’d rather you never have to really scrutinize political stances you’ve taken without even realizing they’re political, and they’d rather you never be challenged by experiencing “SJW politics injected artificially into games” as though social justice wasn’t a laudable end to itself, as though pro-social behaviour wasn’t already a major part of humanity’s evolutionary history.

Of course, you’re free to play other video games pacifist too. You can beat Super Mario Bros without hurting any enemy, excepting Bowser. (Who returns over and over, so clearly you’re not doing him permanent damage.) But when it’s easier to get through the game by defeating enemies, and those enemies are dehumanized, and the game doesn’t bother to provide you with any verb OTHER THAN murder, it’s obviously less your fault than it is the game designers when you only ever murder any enemy.

There’s a lot to be said about a video game that can successfully make demands of us about certain conceits and then drive home the ultimate implications of those conceits in such a thorough and all-covering manner. Toby Fox has, with this game, proven to me that he has several major talents: game music composition, game narrative, and philosophy. Maybe the graphics belie all that. Maybe they’re intentionally simple to show that people can come to love video games — can come to vote for them as “Best Game Ever” — despite simplistic graphics, despite simplistic game mechanics, despite a veneer of being very little more than a simple JRPG about a simple human trying to escape an underground full of monsters, like every other game pitting a lone human against a horde of monsters that’s ever been made.

Undertale is a game that’s profoundly affected me in ways I wasn’t expecting, and has galvanized me in applying my morality to other video games. And that’s saying something — I have a very finely tuned and I’d like to think pretty solid sense of morality as it stands, as evidenced by the past ten years of my blogging about social justice. I care deeply and passionately about trying to achieve the best end for the largest number of people and it kills me when any situation is anything less than the most optimal for as many parties as possible. The fact is, Undertale actually made me question how I play other games, and that’s significant. I have a hard time playing evil runs in most games as it stands, but Undertale entirely kept me from doing it altogether.

Of course, it spared me no moral outrage, when during the Genocide run — which I watched someone else do on Youtube — there were choice words about people who were too weak to be able to kill everyone in the game themselves but were willing to sit by and watch someone else do it.

And, he’s right. If you’ve accepted any of the rest of the conceits of the game, that this is a universe where it’s best to be kind and to try to save everyone, that this is a universe where you are the only one with any agency, that this is a multiverse where every decision point results in a universe state where real characters experience real pain, then you’re sitting by and allowing someone else to doom not only all the monsters, but all humans and all of reality. That is pretty monstrous.

Except, this has already happened. Every possible iteration in a multiverse exists simultaneously. You can steer each installation to your preferred endstate and leave it that way, but you can’t do much about other people’s endstates.

But your control over the endstate of your own game extends beyond the conventional. Yes, you can reset the game, but in theory, you could also delete files on the system to do a full reset and purge your locale’s timeline of ANY consequences, including of having performed the genocide run. You have such complete control in a meta way that you could alter circumstances even beyond what Toby Fox intended.

Except, he probably also intended that. The clue to that is how you get access to the game’s biggest secret, which I’ve alluded to before — you can edit the game files and gain access to… no. I won’t say. Creepypasta-level stuff, and you need to see it for yourself.

Undertale is a hell of a lot deeper and meatier than the plot of almost any other game I’ve ever played. It’s a game with simple binary choices that feels like the consequences of each choice are very significantly more important and more portentous. It feels like you’re steering a little pocket universe, and choosing to tell Undyne that anime isn’t real is an action that would legitimately break her heart, and choosing to comfort Napstablook and make a friend is worth your time, and choosing to complement the skeleton on his spaghetti-making skills is actually IMPORTANT — important in a way that sealing that fiftieth fade rift in Dragon Age: Inquisition isn’t, even though any fade rift generates demons that could kill people around it. It’s a game that got the personal scope dialed in so perfectly that you honestly care about each character, no matter how small. You are charmed by Shyren opening up and sharing her songs with the world. You truly believe in Vulkin and your telling it so comes naturally. You help Temmie go to college. You ‘ship the Royal Guards. Every tiny action means something. Even if it doesn’t mean much in terms of the game state, it really means something.

Honestly, Undertale is the first game I’ve played that managed to make me feel that way about any of these bits being shifted around in a game. I recognize all the same patterns as in other games, all the variables that need to be toggled to get the end game state just perfect for everyone, and I’m genuinely motivated to try for each character’s best outcome. I honestly can’t praise the game enough, for that fact alone. It’s the first game with an overt and mostly-binary morality system that actually has meaning, even if the mechanic is “kill or don’t”.

If you’ve read through all of this, and you still haven’t been convinced, I’ve got nothing.

It’s… got dogs? You can date a skeleton? I mean, what more could you want?

Interesting that you assume Frisk is male…their gender isn’t ever specified that I recall.

It was partway through my first, pacifist run that I decided I simply could not do a genocide replay. What I wasn’t expecting was to boot the game up a few months later when my spouse started playing so that I could keep up with them (intending another pacifist run). After Flowey’s message I…just couldn’t.

Feeling the moral impact of decisions in a game is nothing new to me. If the game is structured to allow for nonviolent or nonlethal (or less-lethal) approaches to opposition, then resorting to lethal methods can literally make me feel nauseous. (For some reason, if the game is not structured this way, I have no problem mowing through enemies. I can clear dozens of enemy troopers in the Mass Effect series, knowing I did my best to talk them down first). This started sometime between playing Deus Ex, where nonlethal tactics were necessary simply for stealth gameplay, and Metal Gear Solid 2, where I watched a friend gleefully smear a soldier’s blood over a hallway and I realized I simply couldn’t find that fun. This is also why I felt so betrayed by the way Fallout 4 did almost nothing with the Charisma stat.

If I implied Frisk is male anywhere in the body of this, it was an accident — Frisk is canonically “they”, agender, so people could more easily self-insert if they’d like, or could assume they’re whatever gender they prefer. I do, however, assume Chara is male. Toby set up the naming screen such that you’re probably going to give them your name, and I’m male. On my run, the first fallen human’s name was, indeed, Jason. And since I wasn’t actually naming Frisk, I’m happy to assume Frisk is still agender.

Chara goes by they/them pronouns. Asriel, at least, refers to them that way, and Asriel knew them for long enough that he should know.

Perhaps I wasn’t entirely clear. Toby Fox intentionally set up Chara and Frisk with “they” pronouns to facilitate self-insertion, so given pronouns don’t clash with your own. However, when you “self-insert”, you’re only actually doing so with Chara. Chara may be their “true name”, but if you name the first fallen human after yourself, you’re by implication also giving them your gender. In my run, Chara was Jason, me, male. I didn’t get any choice about Frisk — you DON’T get any choice about Frisk, ever.

But I’m perfectly fine with Chara still using they pronouns, even if he was male in my run. I’m also perfectly fine with Chara being other genders in other people’s runs. This is a multiverse, after all.

True enough.

I’m still disappointed that Toby took out the option to date Mettaton.

I tried to do a genocide run, but it was alternately heartbreaking and incredibly boring. I eventually just gave up, which I like to assume made at least Sans feel better…

I’ve been trying to get the creepy secret, but don’t seem to be able to. I think I’m missing something…

As for Frisk, it’d be nice if there was actually a non-binary character in a game. I’m not sure exactly what Toby had in mind (self-insertion compatibility or actual non-binariness) I prefer to think of Frisk as actually non-binary, since I am and we get no representation in anything.

I heard so much good about Undertale that I decided I had to check it out. Sadly, I did catch a light spoiler before I played it so after the initial fight with Toriel I did the pacifist run, and with a little help from Google managed to get the “good” ending.

Unfortunately, I found the game just a little too boring and the characters just kind of annoying. I felt all the happy feels at the end when everybody joins the fight against Flowey, which was fun. I also got the feeling that there was more going on in the background than I noticed, but after I got the ending I just couldn’t be bothered to go back and do it again.

I see there was definitely much more going on under the surface than I thought.

I’d recommend the game because it does a good job of tossing the oh-so-familiar video game progression mechanics on their ear, but otherwise I found it kind of boring. Maybe it would’ve been different if I’d played it sober instead of late at night after a couple of homebrewed beer sessions.

Siarl – but there are nonbinary characters! Monster Kid, the Dummies, and Napstablook all go by they/them, and that isn’t an exclusive list so much as what I came up with off the top of my head.

As for the creepy secret, you have to meddle with the code. Alternately, check the internet.

Mettaton’s canonically trans, but it’s definitely not plain what gender they are transitioning from (when they were a ghost) and what gender they’re transitioning to in the new robot body, only that that body is beautiful. As far as I can tell, Mettaton’s gender is “legs”. Which, I suppose, is traditionally female-coded — but there’s nothing about their presentation that’s explicitly male or female. I’d say they’re definitely non-binary.

Though, I suppose, Mettaton’s old house is decked out in pinkish stuff. Doesn’t necessarily mean they were female as a ghost before getting a male trans body, though. Could be Mettaton (Mettablook?) was decorating for the gender they felt they were, rather than the one they were assigned at… ghosting?

Hrm. Looking at scripts, others refer to Mettaton with he/him/his pronouns. So, transitioned to male, but a very non-binary presentation of male.

Here I am, multiposting on my own blog. Author’s privilege.

Considering the only other ghost we know of (Napstablook) is they/them, and ghosts don’t have the kind of biology that leads people to “you have X so you must be a girl”-type labeling, I wouldn’t be surprised if ghosts didn’t involve themselves much with gender in general. We don’t have assigned-nonbinary-at-birth so much in real life, but that might have been the case for Mettaton, or maybe there wasn’t a gender transition so much as he really wanted dem legs and the transness was just in allegory, or something. Eh, not really a fan of the second option actually.

I love Undertale for how it trashes all over these ideas about what games in stories can be and what gamers want from them.

Like, the idea that gamers want consequences for their actions. Really? Okay, here’s one. If you go out of your way to kill everyone in the game, which is a harsh, nearly impossible task that you cannot fall into on accident, a cutscene at the end is altered slightly. That’s it. Everything else is the same. It is the smallest of consequences, literally an eye sparkle, yet people broke into their games to reset that one, singular effect their actions had had on the game, getting angry when the change had been saved onto steam. Gamers didn’t want their actions to have consequences, they wanted the opposite. To be able to see consequences and go back and forth on them as they please, making them every bit the capricious God that Flowey was at his worst and he begs the player not to become.

I love the way the genocide run is this awful slog. Everything about it is terrible. Characters implore you to stop, grinding takes forever and your strength makes it super boring, but bosses spike in difficulty can make careless item management a lethal mistake.

A lot of people knew that there was nothing at the end of the tunnel. They could just look up the ending if they wanted to, and many did. The experience is awful, difficult to the point of extreme frustration, an emotional assault for those who fell in love with the characters, and the only result their effort will show is that those characters can never have a happy ending again. Yet people do it anyway. What does it say about us that we put so much effort into something so futile, and that those who haven’t are considered not to have beaten the game?

I’ve had conversations with people who insisted the genocide run is too difficult, as it locks off content from people who don’t have the skill to beat it. I think that is actually an amazing feat of meta narrative, as there are people the game manages to beat, staving them off from wiping out the world.

Undertale’s use of tricks only games can pull of made me appreciate it so much more, and the way it forces us to look at ourselves and the narrative we’ve spun around playing and beating games is something that blew my mind when I first realized what it was doing.

Sharkjack — the cutscene you’re referring to is only if you “sell your soul” to reset the game after a genocide run, then play through full pacifist again. It’s more to remind you that you don’t get the unambiguously happy ending if you were a monster at any point in the past. Your world state is thoroughly tainted — the world remembers what you did. It is one last gut punch for the people who think they’re “above consequences”. And, yeah, the consequences being a mere eye glint is so seemingly minor, and yet it sends people into fits trying to claw back against the world state and undo what they did. Why? It’s an eye glint and some creepy music. Masterful emotional manipulation.