Most of the stories in Shifty Lines are and will be about separatist conflicts. Particularly in Africa, though, the simple separatist concept does not accurately reflect the goals of the border-rearrangement movements. While this is fairly obvious in North Africa, where two of the major ethnic groups with nation-state aspirations are spread across multiple countries, eastern Africa presents a different case. In East Africa, like the Caribbean, a large-scale effort to combine several countries into a single federated state is underway, and stands a decent chance of success.

Africa’s Great Wave

The defining event of Africa’s linguistic history is the Bantu expansion. Africa remains an extremely linguistically diverse continent, befitting its status as the birthplace of Homo sapiens, but a single language family dominates its entire southern half. The Bantu languages, a subset of the still-larger Niger-Congo family, arose in what is now Cameroon in western Africa circa 2000 BCE. Over the next 3700 years, Bantu-speaking groups spread eastward and southward, assimilating and displacing earlier Pygmy, Khoi-San, Twa, and other hunter-forager groups as they expanded. They were unable to move northward, hemmed in by their powerful Niger-Congo kin in modern Nigeria and by the Afro-Asiatic behemoths of Ethiopia and Egypt. As they expanded, they differentiated into a multitude of distinct ethnicities with their own languages and customs, while retaining the commonalities that make them an identifiable language and culture group today. They also acquired farming and animal-husbandry practices from their Afro-Asiatic neighbors and spread them far to the south and to the hunter-forager societies they overran.

The Bantu peoples appear to have become established in what is now East Africa by 500 BCE, beginning with the Urewe civilization around Lake Victoria. Within about 600 years, in the first century ACE, coastal Bantu societies began receiving Arab traders and, from there, links to Greece, Egypt, and Iran. The trading posts they established became large cities and city-states and became key stations in an Arab-mediated trading network that grew to include Madagascar, India, and the Malay Archipelago. Starting in 700 ACE, as the Urewe civilization fell, Islam began to spread through these city-states, in particular to and through their often Arab or Persian rulers. The Swahili language (known internally as Kiswahili) formed as a lingua franca incorporating Arabic, Persian, and Malay vocabulary into a Bantu base. This language gained more and more widespread use as the trade network expanded inland and involved more of East Africa’s kingdoms and tribes. Notably, the Indian Ocean trade included a large-scale slave market that sent East Africans to Arabia and India long after the British ended their involvement in the slave trade elsewhere in Africa.

Idioma suajili” by Fobos92 – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

(Dark blue is the region where Kiswahili is spoken natively and/or is already an official language. Light blue is the region where Kiswahili is spoken as a lingua franca or where extremely similar languages are spoken.)

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, Nilotic peoples from what is now South Sudan began moving south and east into East Africa. Mostly pastoralists and often nomads, these people diversified into numerous tribes as they expanded into Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, displacing pre-existing Bantu groups as they moved. Many, such as the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, are still regarded as interlopers in the region by their Bantu neighbors, especially since they arrived in East Africa later than the first European explorers and often cooperated with Europeans to secure more territory and influence for themselves.

Europe’s Eye

In 1498, the first Portuguese explorers arrived in East Africa and later reached India. Vasco da Gama’s arrival created a sea path between Europe and India that challenged earlier routes through the Red Sea and the Sahara Desert. Portuguese control over this route was limited, hotly contested between them, the British, the Dutch, and the Omani Arabs whose presence in the region preceded them by centuries. The Portuguese would abandon their designs on East Africa north of Mozambique within a century, allowing the Omani Arabs to consolidate their hold on the coastal city-states. Oman even moved the seat of its empire from the Arabian city of Muscat to Zanzibar, an island off the coast of what is now mainland Tanzania, in 1839. By 1850, however, Oman’s economy was severely weakened by the British abolition of the slave trade and by conflict with the Ottoman Empire, enabling the British, French, and Germans to spend the next 40 years claiming protectorates and colonies over swaths of the East African coast, eventually including Zanzibar itself and the outlying Comoros.

From there, European control expanded into the interior of the continent. Kenya received large-scale settlement and investment, including rail construction by Indian laborers, which would leave Kenya consistently better off than its neighbors thereafter. However, British attentions in Kenya also included forcibly relocating native groups to make room for white settlers. Africans also had their land claims denied and were systematically excluded from the growing colony’s government until 1944. In what is now Uganda, the British maintained a protectorate for much longer, relying on the powerful Buganda kingdom to collect taxes and exert their will over Buganda’s weaker and increasingly resentful neighbors. Germany treated German East Africa (modern Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi) as a source of income and used extreme violence to keep African farmers producing cotton for export, inciting the Maji-Maji Rebellion in 1908. Germany would lose the colony following its defeat in World War 1. It was split between Britain (Tanzania) and Belgium (Rwanda and Burundi). Much of the rest of Kiswahili-speaking Africa was part of what would become the Democratic Republic of the Congo, combined with large Kikongo, Lingala, and Tshiluba-speaking regions under the brutally authoritarian ownership of King Leopold of Belgium and, later, a less brutal Belgian colonial regime. The remainder of Kiswahili-speaking Africa is thin strips of adjoining Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia, and Madagascar where Kiswahili is still useful as a trading language but whose cultural affinities lay elsewhere.

Independence

The East African colonies all gained independence within a few years of each other in the mid-20th century: DR Congo in 1960; Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi in 1962; Kenya in 1963; Tanzania in 1964, and Comoros in 1975. These movements had much in common with one another. In all cases but Tanzania, independence came after drawn-out warfare with the colonial power and led to the mass exodus of white settlers (though not white soldiers, in the Congo’s case). The independence movements typically involved some Cold War power plays between the Western and Soviet blocs, as each tried to lure in the new countries and keep them out of the other’s orbit. They did not change the borders of the new states and rarely shifted power away from colonial-era favorites such as Uganda’s Buganda and Rwanda’s Tutsis. In parts of the region that had large, wealthy, influential South Asian populations brought in by the British, Uganda and Kenya in particular, discriminatory citizenship laws and other racist measures disenfranchised, expropriated, and otherwise told those people to leave, leading to their mass exodus from East Africa to Britain.

Recognizing their cultural affinities, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania established the East African Community in 1967 as the successor to the various colonial institutions the three colonies shared until then. This initial effort collapsed in 1977 because of differences between Uganda’s Idi Amin and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and the massively different economic systems of Nyerere’s socialist Tanzania and capitalist Kenya. The episodes of horrific, bloody violence and dictatorships that engulfed nearly all of East Africa from the 1970s until recently certainly did not help:

· The violence took on a more overtly ethnic dimension in Rwanda and Burundi in particular. The loss of Belgian patronage enabled the Hutu majority to assert themselves in both countries. The resulting back-and-forth of demands for retribution turned into civil wars, and civil wars turned into genocide. In Burundi, this proceeded in two separate events (one in the 1970s, another in the 1990s), whereas Rwanda’s genocide transpired over several months in the 1990s. The Hutu Power movement and Coalition for the Defense of the Republic in Rwanda set about to purge Rwanda of Tutsis, the largest minority group of Rwanda and Burundi. Conversely, the Tutsi-majority Burundian army called on and received Congolese support for the extermination of Hutus in Burundi. After arming the civilian population for months with machetes and other weapons and assassinating the presidents of both Rwanda and Burundi, the Hutu Power leaders started within hours a widespread campaign that was the first in the world to explicitly call itself “genocide.” (Other sources insist the president of Burundi was killed by Tutsi extremists.) The Rwandan genocidaires, most of whom were those civilians, slaughtered Tutsis, moderate Hutus, and anyone else who stood in the way of a Hutu-only state at a rate five times higher than Nazi Germany. Their targets including those who pointed out that the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was almost certainly one of caste or lifestyle rather than race. The Rwandan Patriotic Front, a Tutsi refugee group founded in Uganda, halted the genocide whenever it managed to gain or keep control of a region, but the UN mission sent to halt the killing did not have the authority to actively oppose the Rwandan army, severely limited its effectiveness. In the end, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people were killed in Rwanda in the three months the genocide was in effect, and thousands to millions more women subjected to war rape and subsequent HIV exposure to themselves and their children. Thousands more died in diseased squalor in refugee camps in all four neighboring countries. Despicably, the French aligned themselves with the Hutu regime in order to suppress “Anglophone influence” in Rwanda. In Burundi, about 750,000 people were killed between the two genocides, intervening civil war, and other crises. Operations by both sides intruded into neighboring Congo (then Zaire), setting off the First and then the Second Congo Wars and maintained the violence in East Africa for another several years. The Rwandan Genocide features prominently enough in the Rwandan popular consciousness to lead to a massive overhaul of the Rwandan political system and the occasional revisionist movement positing a Tutsi “counter-genocide” against the Hutus, as was seen in Burundi.

A Modern View

Much of the violence of East Africa is behind it. The forces that made the region a continuous maelstrom of gunfire and mutilation in previous decades are, by now, much quieter, and manifest instead in continued ethnic rivalries and contested elections throughout East Africa. Still, much of East Africa is still only beginning to recover from the years of civil war, genocide, and dictatorship. Internal connectivity between large cities like Kampala and Mombasa and more remote regions of each country is still minimal, and democracy is often weak in countries that have no more than a generation of stable rule behind them.

Nevertheless, the democratically-elected leaders of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda re-established the East African Community in 2000 after working on and negotiating over the process since 1993, with the explicit goal of eventually combining the three countries into a single East African Federation. Rwanda and Burundi joined the Community in 2007. Progress toward that goal has been slow. Initial plans hoped to have the federated state established by 2015 and the common currency, market, passport, and similar measures in place long before then, but implementation has been far slower than this incredibly ambitious agenda. The customs union was not implemented until 2005, and only Tanzania has ratified the EAC Monetary Union Protocol as of 30 June 2014. That being said, the East African Community does maintain a common East African Court of Justice for regional issues, a single body for coordinating policies related to Lake Victoria (which borders Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania), and other institutions that keep the five current members on the path to unification. The operation has been successful enough that neighboring states have taken notice and asked to join, making this a project with incredible potential.

Growth

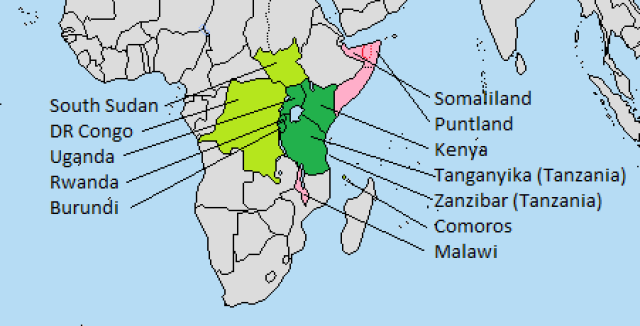

The core Kiswahili-speaking region is already within the East African Community, but the periphery may yet join the growing organization and the country to come.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo as such has no place in the EAC or in the upcoming EAF. The eastern Congolese provinces of Maniema, Orientale, Katanga, North Kivu, and South Kivu are the westernmost extension of the Kiswahili zone, however, and speak the lingua franca with far greater enthusiasm than even Rwanda and Burundi. The cities of Goma in DR Congo and Gisenyi in Rwanda have effectively amalgamated into a single metropolis, bringing their immediate surroundings into the EAC’s orbit by default. If the Democratic Republic of the Congo were to disintegrate, the resulting smattering independent states might include future supplicants to the East African Community. Katanga and the Kivus have already hosted independence movements with the potential to lean in that direction, although these have appeared to be focused on clashes over the destination of the area’s massive mineral wealth rather than nationalist aspirations.

It is likely, however, that the eastern, war-torn region of DR Congo is as yet far too undeveloped for the still-precarious community to absorb, before or after the Federation forms. Whatever event causes the Congo to fragment is unlikely to make that any easier for the enormous country’s better-off neighbor to process. The region would also have to add English as an official language, as Rwanda and Burundi are currently implementing, in order to harmonize its operations with the rest of the community. This would be no small feat in a region hosting millions of Francophones and in which the French language has been instrumental in maintaining what little unity DR Congo can claim.

Comoros

The Comoros Archipelago is a particularly interesting candidate for East African Community expansion. The last part of eastern Africa to lose its Arab sultans, Comoros is a member of the Arab League and maintains much stronger ties to the Arabian Peninsula than any region of the EAC, with the possible exception of Zanzibar. The local language, Comorian, is alternately regarded as its own tongue or a dialect of Kiswahili and is written with the Arabic script that mainland Swahili abandoned during the colonial period. Like DR Congo, it is also a Francophone rather than Anglophone state, and the ongoing struggle over Mayotte keeps Comoros continually entangled with its former colonizer.

The possibility of accession into the East African Community and subsequent Federation would give the three fractious islands a chance to reorganize themselves. Becoming part of a larger federation would enable the islands of Grand Comore, Anjouan, and Mohéli to separate from one another without having to function entirely alone, and to deal with each other the same way they deal with more distant fellow East African entities like Tanzania and Rwanda. This would also give the economically weak, politically chaotic, and isolated islands much greater access to the burgeoning East African economy, to mutual benefit. This would most likely require the islands to reject their tie to the Arab League in favor of a firmly Afrocentric political approach, however, which is likely to be less than appealing.

Sudan and South Sudan

Sudan formally applied to join the East African Community in 2011, but their application was rejected out of hand, and with good reason. As an Arab-majority state with a history of Arab nationalism, enormous violence toward its black African population, and (with the independence of South Sudan) no land connection to the existing EAC, Sudan has no place within the growing community.

South Sudan is another matter. Africa’s newest country is overwhelmingly Nilotic in ethnic composition, and is the northernmost extension of the ethnic homelands of several groups that extend into Kenya and Uganda. Trading relationships between the northern Kenyan and Ugandan societies and what is now South Sudan are longstanding, and South Sudan has embarked upon a dramatic pivot of its foreign relations with independence, seeking to increase ties with its southern neighbors and distance itself from its former Sudanese masters. Interestingly, the region was very nearly part of a greater Uganda under the British, before a last-minute change in administrative priorities instead appended it to British Sudan. Kiswahili has, as yet, only a small presence in South Sudan, but that presence is growing rapidly as Sudanese refugees previously residing in Kenya and Uganda return home and bring their Kiswahili proficiency with them. As South Sudan lacks an African national language and currently relies on English to keep its dozens of ethnic groups talking, Kiswahili may prove to be important in the new country’s self-conception.

Kenya and Uganda extended South Sudan a pre-emptive invitation to apply to join the East African Community upon its independence, and South Sudan has done so. However, South Sudan’s memories of civil war are twenty years more recent than Rwanda’s and South Sudan still depends on oil pipelines ending at the Red Sea for the overwhelming majority of its economy. The EAC maintains that South Sudan would be better served growing its economy and nursing its wounds as an independent state for a while yet before joining, lest it become firmly subordinate to healthier states like Kenya in a united country with free movement of goods and skilled professionals. It is not clear whether this statement is genuine or represents an animus toward allowing an increased presence of Nilotic peoples in the majority-Bantu Community.

Somalia

Like South Sudan and Sudan, Somalia has lodged an application to join the East African Community. The EAC’s web site lists the application as pending, Wikipedia claims it was rejected in 2012, and the Sudan Tribune notes it and South Sudan’s applications as “deferred.” Kiswahili is a relevant language only in the southernmost coastal tip of Somalia, and Arabic and Somali hold sway everywhere else, making Somalia’s cultural credentials dubious at best. However, Kenya’s eastern region is majority Somali and once fought to be included in Somalia rather than Kenya, and southern Somalia is also home to a “Somali Bantu” cultural group that is the descendants of Tanzanian and Mozambican slaves. Kenyan soldiers have been instrumental in helping the Somali government regain control over its southern, Islamist-dominated regions. In politics, if not in culture, there is a connection between Somalia and its southern neighbors.

Malawi and Zambia

Tanzanian officials express interest in expanding the East African Community even farther, to the nearby states of Malawi and Zambia. However, Malawian accession to the community has not been discussed at any official level. Malawi and Zambia were once united with what is now Zimbabwe as the Central African Federation, and feature Kiswahili speakers only in narrow border fringes near Tanzania. The only relevant cultural link either brings is Malawi’s long shore on Lake Malawi, which would give the EAC an even greater share of the African Great Lakes system, especially if the Community were to also acquire the five Congolese Swahili provinces. Malawi’s dense population might, likewise, benefit from being able to spread easily into a much larger area, but this is not likely to meet with Tanzanian approval. Neither country is a likely candidate for part of any future federated state.

Looking Forward

The East African Federation is not an irredentist project like a united Albania, Azerbaijan, or Maghreb. It is a very intentional effort to turn a shared trade language into the basis for a campaign of ethnogenesis. Like pre-unification France, Germany, and Italy, East Africa is a series of often very distinctive cultures united by the shared lingua franca of Kiswahili, which the majority of the region learns as a second language rather than a first. For the other peoples of East Africa, it is a language with a long history of use in inter-group communication but essentially no relevance within groups. Inside a given region of East Africa, Luganda, Kinyarwanda, Kikuyu, and other local languages are generally much more important. The leaders of the region have seized upon this Swahili heritage as a means to convince the peoples of East Africa that they have a shared heritage, culture, and destiny, and hope to harness that energy to build a large country on African terms rather than the colonial terms that usually define large countries in Africa. The concept is, in that sense, similar to and much more sensible than the Rainbow Nation concept that unites South Africa, and stands a fighting chance of slowly erasing distinctions like Hutu-Tutsi that have been the basis of enormous violence.

The concept faces major problems, though. The peoples of East Africa nearly all have their own languages and identities, separate from Swahili and in some cases associated with their current national boundaries. In Kenya in particular, large populations of non-Bantu peoples such as the Somali, Maasai, and Oromo do not feel the same cultural links that their Bantu neighbors do, trade language or no. This will increase dramatically if South Sudan is added to the prospective union, as South Sudan’s people are virtually all of Nilotic rather than Bantu heritage and avowedly come to Kiswahili as a second or third language. The region also has major religious divisions. The coastal regions have large Muslim populations, with overwhelming Muslim majorities on the Zanzibar and Comoros Archipelagos, Muslim-majority coastal strips in Kenya and Tanzania, and Christian and African-religion majorities elsewhere in East Africa. Uganda and DR Congo face rapidly expanding evangelical and Pentecostal denominations with theocratic tendencies already reflected in Uganda’s government, which will be difficult to sell to coastal Muslims. A fully united East African Federation would be a single country hosting both the Lord’s Resistance Army and sympathizers of the Al-Shabab Somali islamist insurgency, a terrifying combination that can spell only tragedy for East Africa’s atheists, animists, polytheists, and queer community.

Another complication is that the countries currently being pulled into the East African sphere have different colonial histories. Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and Tanzania are all former British possessions, but Tanzania was German for some time and South Sudan under the yoke of Arab-nationalist Sudan. The other Swahili-speaking regions of Rwanda, Burundi, and the eastern third of DR Congo instead have a small German and large Belgian history, and use French as their colonial language instead of English. Rwanda is moving to make English and Swahili much more prominent within its borders than they have been in pursuit of the EAC’s goals, and any future applicant to the EAC and especially the East African Federation will have to do likewise. Similar difficulties continue to complicate the ongoing effort to harmonize laws between Tanzania and Kenya, whose dramatically different political directions in the 1970s and 1980s mean their laws have much to discuss.

Still, the East African Community and eventual Federation provide the region with a chance to shed boundaries imposed on it by European powers. In particular, a single federated state provides this fractious region the opportunity and perhaps the necessity of dividing the existing states into smaller units so that their populations do not overwhelm each other, and so that existing cultural groups do not fear vanishing under several layers of institutional erasure. Kenya already has a Luo-majority province—what if that province joined Luo regions in Uganda and Tanzania into a single Luoland? What if the kingdoms of Uganda again became distinct entities? What if Zanzibar again separated from Tanganyika and Anjouan and Mohéli from Grand Comore? Such internal reorganization has the potential to help solve the more conflicted regions’ grudges by allowing them to keep their grudge-mates at the same distance as more distant neighbors, while still giving them the benefit of overall unity. In this way, an internal rearrangement of the future Federation’s parts may resemble India after the States Reorganization Act, with the additional benefit of enabling future applicants to join a community of similarly-sized colleagues. Otherwise, the Comorians and Malawians may rightly wonder if they aren’t simply annexing themselves to Kenya and Tanzania, rather than joining a community as nominal equals.

A united East African Federation could also form the nucleus of a wider East African Community that includes neighboring independent states. Ethiopia has no interest in subsuming its history of hard-fought independence and Ge’ez distinctiveness into another independent state, but it might be willing to follow Somalia into a cooperative arrangement with the massive new country to its south. This is probably a better arrangement for Somalia and its breakaway segments of Somaliland and Puntland than joining their distant, mostly Bantu neighbors.