Proposition 60 looks great at first glance. I wouldn’t fault anyone who doesn’t know anything about it for voting “yes” if that’s all they knew about it. I can easily imagine myself getting suckered into voting for it if I didn’t have such strong connections to the sex worker communities. But the fact is, it’s a lousy law, the latest in a long string of attempts by the AIDS Health Foundation to profiteer off the fear of sex and the stigmatizing of sex work. I want to talk about why it’s a lousy law here, but I want to do more than that, too: I want to use it as a demonstration of why it’s important for everyone in this country who works for a living to pay attention to the organizing efforts of sex workers and support them.

California Propostion 60: Why It Doesn’t Pass the Smell Test

The case for Proposition 60 depends largely on selling a very distinct picture of the industry to voters, one in which there is a clear, firm line between heartless management and desperate workers. But the internet has blurred that line for porn workers as it has for so many of us. While large companies like Wicked, Vivid, and Kink.com are still powerful economic forces, they’ve diminished in importance.

Nowadays, most performers are also producers of their own material. Almost any adult performer worth the name maintains a website of their own, complete with photo galleries and video clips. Many shoot and sell their own material on third-party sites like Clips4Sale or God’s Girls without the oversight of a traditional studio or producers. Independent, self-produced porn has gone from being a niche market to being one of the dominant models in adult entertainment. The day of the cigar-chomping mogul is as obsolete in porn as it is in mainstream film.

Where Proposition 60 is concerned, this reality isn’t just a matter of optics: It determines who the law punishes. Performers who shoot and distribute their own material are subject to prosecution under the law if condoms aren’t visible in their films. The limited media coverage of this point has focused on the argument that married couples who make porn in their own homes could be sued for not using condoms. That’s a legitimate example, but it misses one of the most important points: The porn workers who are most likely to be targeted by such a clause aren’t going to be married, hetero cisgender couples, but those with the most marginalized identities.

The big production companies tend to favor the most conventional, privileged kinds of bodies: slim, white, and cisgender. Those who are fat, transgender, people of color, or otherwise fall outside of conventional beauty standards are more likely to have to rely on carving out their own alternative channels of distribution in order to make a living.

Besides who it targets, the enforcement mechanisms of Proposition 60 are weird and poorly thought-out. If the state doesn’t act on a reported violation, any Californian is able to act as plaintiff and sue the producer for not showing condoms in their film. If the lawsuit is successful, the plaintiff — who again, can be any Californian who watched a porn film and didn’t see condoms being used — gets 25% of the judgement. Fines can go up to $70,000 for repeat violations, which is a pretty strong motivation to sit around watching porn that doesn’t turn you on.

In its editorial opposing Proposition 60, The Los Angeles Times called the law “heavy-handed,” especially because of the enforcement mechanism:

Proposition 60 is far worse than Measure B not just because of its unusual provision allowing any Californian to sue and collect damages without having to show that they suffered any harm. It also extends the financial liability to, potentially, small-time performers who produce and distribute their own content (and who are unlikely to have been coerced into not wearing condoms). There’s also the possibility that some people might use the new law to harass adult-film performers.

Rewind: The CalOSHA Fight

Last February, over 100 sex workers came to Oakland to speak before a meeting of the California Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s board. Before the board was a proposal to create and enforce safety standards that would require all adult movie performers to wear not only condoms, but goggles, gloves, dental dams, and other prophylactics while shooting any sex scene for the cameras.

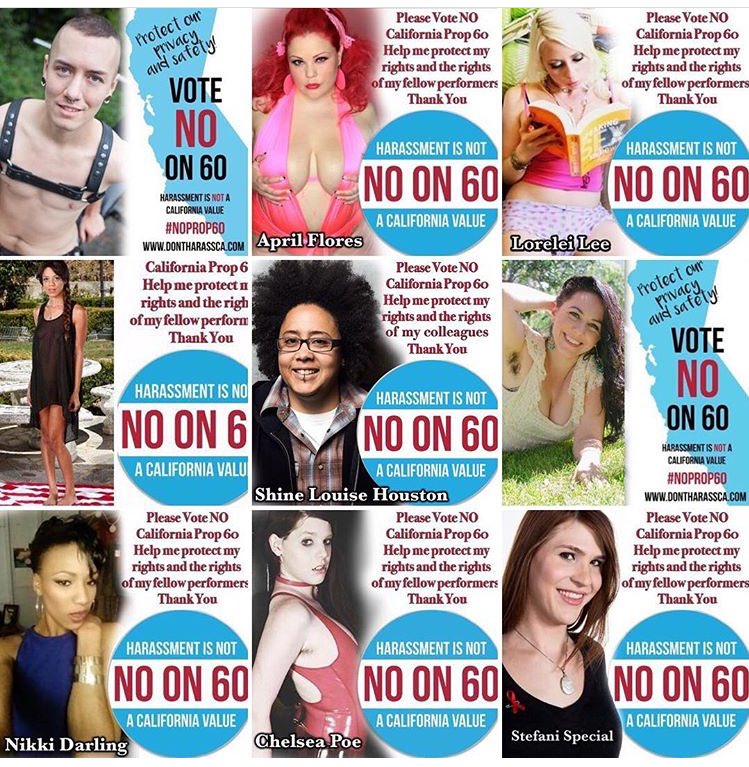

The proposed standards were ostensibly meant to protect the health and welfare of sex workers, but there’s one catch: The workers themselves neither asked for nor wanted the new guidelines. For six hours, adult models, film stars, webcam performers, and others came up to the microphone and explained to the board that not only would the standards fail to protect their health, but would destroy their livelihoods by driving porn studios out of the state, and endanger them personally by making their names and personal information part of the public record.

The day wound up being a rare and much-needed victory for sex work activism: the CalOSHA board defeated the standards by a single vote. However, the fight neither began nor ended that day in Oakland. The fight over condoms in porn started as a local one in 2009, when the AIDS Healthcare Foundation began agitating for Los Angeles County to pass an ordinance that was essentially the same as the guidelines that CalOSHA voted down in February. They won that fight when Los Angeles passed Measure B in 2012. The result was not an increase in safety for porn workers, but a mass exodus of productions from Los Angeles County.

My home in Berkeley is about seven miles away from where the confrontation with OSHA took place. Because I was already treading water with work and family commitments, I didn’t attend. I regretted that then, and I still do. It was an important chapter in a political struggle that I’ve followed and written about for years, but even more importantly, the people fighting for a voice in the governance of their workplaces were friends of mine. For days before the showdown, my social media feed was filled with reminders about the meeting, urging as many people as possible to turn out and show their support.

I’m not a sex worker myself, and never have been. But I do think that the fact that I’ve been lucky enough to have many of them as friends, confidants, and role models over the past 25 years is very important in making me the person I am now. Knowing the boundaries when hanging out with a friend you’ve just watched in a porn video is a great way to get a more sophisticated understanding of consent than you’ll get on talk shows or advice columns. I’ve learned volumes more about keeping myself and my partners safe and healthy than I would from any mainstream source.

But all the escorts, strippers, nude models, pro-dommes, and porn stars that I’ve known have taught me about more than sex; they’ve made me think at least as much about work, and the role that it plays in our lives.

Sex Workers: Labor Activists For the 21st Century?

The idea of a full-fledged labor movement demanding rights in the workplace now seems somewhat quaint and old-fashioned in the modern United States. Talking about labor activism calls forth images of Henry Fonda and Woody Guthrie in the 1930s, or Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta marching in the 1960s. Those fights are relics of another time, pressed like leaves between the pages of history books, either unrealistic, undesirable, or irrelevant to the concerns of today.

And yet, a vigorous and sustained labor movement, made of people who get naked for money, has been building for the last thirty years. Anyone interested in civil rights and labor in the United States should find the history of that movement not only fascinating but inspiring. From Margo St. James’s founding of COYOTE (aka Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) in 1973 to the modern networks of blogs, online mailing lists and nonprofit organizations, sex workers have fought an uphill battle every inch of the way, and yet achieved remarkable success. In the historic struggles of coal miners, garment workers, and field laborers, they knew that even if their lives and health weren’t valued by society, the jobs at least were considered important. Even the most anti-union politician would never stand up before before a crowd of constituents and declare that society would be better off without clothes or fresh vegetables.

Their issues go deeper and broader than most movements, including not only the right to decent wages and working conditions, but simply to work at all without being arrested. The fight to keep police departments from using condoms as evidence of prostitution has been an urgent one for years, and it’s only within the last few years that activists have begun to see solid gains in cities such as San Francisco and New York. Where such policies still stand, the poorest and most marginal workers regularly face the choice whether to risk arrest or disease.

Sex workers fight for the right to use basic financial instruments, such as credit cards, PayPal, or GoFundMe and other crowdfunding services; for protection from exploitative club managers who pay them as contractors while demanding the commitment level of full employees; to be able to call on the law in cases of discrimination or violence; to be able to rent apartments without “anti-trafficking” laws that force the landlord to evict them; to ultimately leave the sex business if they choose, and not to be shut out of straight work because they were an escort or adult performer. A few years ago, after an Oakland escort was raped by a client, California sex workers successfully petitioned state lawmakers to change the laws that prohibited her from getting victims’ compensation funds because of her work.

But one thing that hasn’t been part of most sex workers’ agendas is mandatory condoms on porn sets; that push comes almost entirely from outside the community. And that single fact is the major difference between the condoms in porn debate and any other labor struggle you can name. All the great advances in labor rights have come about as a result of workers standing up and speaking for themselves. In this case, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation is determined to protect porn workers at any cost — even if that cost is silencing the workers themselves.

The fact that the story is inverted so easily in this specific case says volumes not only about how we view sex, but how we think about work at large. The obsessions, fears, hopes, fantasies and taboos surrounding the workplace are every bit as complicated and overwhelming as the ones that dominate how we think about sex. With either, we’re raised to believe that the path to satisfaction lies down the same simplistic path: “Do what (or who) you love.”

The High Price of Working for Love

Personally, I can’t think too much about doing what I love right now. The realities of the world won’t allow it. I’m writing this from a place of fear; my own fears about work, survival, and having just enough money to keep a minimum of health in my 47-year-old body. A few months ago, the company I was working for laid me off after a change in management. I still work for them, but only part-time.

At full-time, I took home over $2,000 a month, plus health, vision, and dental insurance. Now, after I pay COBRA, I bring home about $600 a month. There is a constant hum of terror in the background of my mind now as I count out money and pills. After getting laid off, I had my first tonic-clonic seizure in over a year. It was triggered by a particularly stupid combination of economics and neurosis that I’ve gone through before: I started skipping doses of anticonvulsants in order to make my supply last as long as it could until my COBRA kicked in. Don’t look for the logic; it doesn’t hold up to even the mildest rational scrutiny, but that doesn’t stop me from doing it when that anxiety starts to crawl around in my brain.

The combination of leaden dread and squirrely panic that makes up my mental landscape these days is familiar to too many people trying to survive the modern workplace. Every so often, my Facebook feed turns up excerpts from Steve Jobs’s speech to the 2005 graduates of Stanford. A popular one is “The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle.” But it seems more cruel than inspirational: When I’m worried about whether I have enough seizure meds to last the week, doing what I love — writing — is almost impossible.

Virtually everything that’s written about sex work in the mainstream media is primarily meant to say one thing to its readers: You’re not like them. It’s because of that assurance that we vigorously question the working conditions in porn studios, dungeons, massage parlors, or strip clubs in ways that would be unthinkable in any other industry.

But the more I know about the politics of sex work, the more I say, Yes, I am like them. The issues that sex workers bring up in campaigns such as this one against Proposition 60 are often the same questions that every one of us should be asking about our jobs and the people that we work for: Questions about whether we have meaningful consent when we decide whether to take a job or leave one; about the health and safety conditions of our workplace; about what is a fair wage for work; about where we are fairly allowed to draw the line between our personal lives and our work lives.

Bring up any of these questions in relation to civilian work, and they’re sure to trigger controversy at the very least. The campaign for $15 wages for workers in fast-food and convenience stores is an excellent example: the backlash was immediate and vicious, as though the workers were attacking our most basic moralities, not advocating for economic reform. Even now, after the $15 movement has started to see success, my Twitter and Facebook feeds regularly fill up with image macros mocking the burger flippers of the world for not realizing how good they have it. Typical images show mangled hamburgers or badly-spelled signs, with superimposed text in Impact font saying “This was made by a person who thinks that they deserve $15 an hour.”

Almost any attempt to talk about specific ways that abuses in our workplaces should be changed or reformed will face a similar response. Labor activism is repeatedly dismissed as either bizarrely naive ideology or attempts to encroach on the liberties of others. Even unions for teachers and transit workers have proven easy to depict as parasitic elitists. No matter how many of us feel the sick dread that comes with living from paycheck to week-before-next-paycheck, we cling to the idea that the best way to get past it all is to “lean in” a little bit more.

What Trafficking Really Means

The reason that the AIDS Healthcare Foundation can so blithely ignore the wishes of the people whose lives their policies would affect is that our culture is reluctant, at best, to see them as workers. No matter how much they organize, no matter how much they write books about their lives, create medical and legal clinics suited to their own needs, or mourn the dead who are merely punchlines to others, there is a steadfast and consistent refusal to see them as anything other than victims who need to be rescued. Their actual words and lives are treated as fraudulent, while organizations like the AIDS Healthcare Foundation are considered credible and authentic.

When sex workers speak up for themselves, the mainstream narrative inevitably casts them either as drug-addicted dupes of pimps and porn makers or overprivileged dilettantes who are oblivious to the real costs of the business. That leaves only people like AHF’s Michael Weinstein to tell the rest of the world what sex workers need. The lurid narratives of abuse and degradation don’t just silence the voices of sex work activists — who do in fact have extensive critiques of the sex industries — but also stifle the chances of actively talking about how much trauma and fear is a part of everyday life in civilian workplaces.

For example, we’ve lost an enormous opportunity to talk about the nuances of migrant labor because “trafficking” has devolved into shorthand for “sex trafficking.” One of the biggest trafficking cases in the United States involved oil rig workers from India who testified that Signal International, Inc. lured them to the United States with false promises. According to the EEOC, “Signal subjected the men to a pattern or practice of race and national origin discrimination, including unfavorable working conditions and forcing the men to pay $1,050 a month to live in overcrowded, unsanitary, guarded camps. As many as 24 men were forced to live in containers the size of a double-wide trailer, while non-Indian workers were not required to live in these camps.”

The EEOC’s lawsuit against Signal, International went to trial in January, 2015 and was settled in December, but it remains obscure to the general public. Politicians and nonprofits don’t flaunt it as an example of the dangers of trafficking; it certainly isn’t used to illustrate arguments that the oil industry is a threat to our national character. The case of the Signal International workers certainly wouldn’t be tucked so cozily out of the way if they’d been brought into the country to dance at strip clubs. But it wouldn’t have been talked about as a labor case, either. It would be a story about sex, a titillating example of the dangers of unchecked lust and greed.

We won’t have an honest conversation about sex work until we can talk about work honestly, and unfortunately, that conversation is arguably even more taboo than frank, honest conversation about sex. It’s terrifying for us to acknowledge just how little control we have over our work lives, and how little “leaning in” matters. For most of us, the only choice is to keep silent about our fears and keep working for as long as our employers will keep us.

The numbers are close right now for the vote on Proposition 60, and nobody can say with certainty where the vote will go. As of this writing, the latest numbers show 40% for, 40% against, with 20% undecided. However, that represents a significant decline in support: A Los Angeles Times poll in September, showed support for Proposition 60 at 55% in favor of the initiative.

We did three rounds of polling on CA Ballot measures, full article in @Capitol_Weekly Monday… but here are the top line results. pic.twitter.com/p2PMlwSNGd

— CA120 (@CA_120) October 21, 2016

The best piece of news is that no matter how passionate Weinstein is about this particular windmill, the California state political establishment doesn’t seem to share his enthusiasm: In 2014, a bill that would have done the same thing as Proposition 60 passed the State Assembly, but proceeded to die in the Senate Appropriations Committee. This year, both the Democratic and Republican parties have voted to oppose Proposition 60.

Whether it passes or not, we civilians should keep watching what happens: Not only because we so rarely listen to what people in the sex industries say about their own lives, but because we so rarely hear workers of any kind advocate for their own interests with so much power and conviction.

I’ve supported the rights of sex workers only partly because of friendship. There’s also a certain element of self-interest: Civilians need to reconsider the way we view not only the work of escorts, porn stars, and pro-dommes, but our own. As the middle class and the workplace protections that sustain it continue to shrink and jobs become more temporary, everyone will need to learn the language of organizing that sex workers already speak so well.

– 30 –

I will probably vote NO on Prop 60. But I wish your article would say more about biology and pathology and less emotional outpouring that beats around the bush.

I agree that this particular law is a really bad idea and I’d vote against it if I lived in California, but you have not made an argument as to why mandatory condoms in porn would be a bad thing. It’s a bad idea if it only afflicts Californians, but in general?

I don’t buy the “let workers decide” argument.

First it smells of Libertarianism, where nothing is out of bounds as long as everybody “agrees” to it.

Second, we mandate lots of work safety people aren’t happy about for reasons that are often not rational but based on our particular views. Lots of professional drivers hate seatbelts, claiming they don’t need them because they are professionals. Construction workers flaunt safety meassures like hard hats and ear protection because they are “girly”. Right now, condoms are seen as “unsexy”. They remind people that holy fuck, yes, sex can have horrible consequences.

Third, choice is always a flawed idea if the choice isn’t free. Technically all sex workers already have the choice to use condoms, but how big are your chances to keep selling stuff if you do?

Condoms are not designed to be worn for the length of time performers are having sex on set. Forcing them to do so can have negative physical impacts on the performer and put them at a higher risk. Please read http://www.huffingtonpost.com/casey-calvert/the-only-worker-prop-60-h_b_12111522.html? and the article Casey links to regarding condom use in porn for a better, more detailed, description of the problem.

Great story and insight of the labor movement in the adult industry. We thank you for equal insight. Would love to speak to you. The IEAU.

Thank you. Great piece and informative from this side of the pond.

[…] AIDS Health Foundation to profiteer off the fear of sex and the stigmatizing of sex work.” * The “Condoms in Porn” Initiative Shows Why We Need to Listen Closely to Sex Workers (The […]

[…] AIDS Health Foundation to profiteer off the fear of sex and the stigmatizing of sex work.” * The “Condoms in Porn” Initiative Shows Why We Need to Listen Closely to Sex Workers (The […]