Are we still, in 2016, seriously considering the question of whether comics and graphics novels are a serious form of literary art?

You may have read the piece of clickbaity trolling by Rhymer Rigby, titled No Self Respecting Adult Should Buy Comic Books or Watch Superhero Movies. Niki did an exquisite rant about it in her Seriously?!? blog, in her piece titled Today in “Old Man Yells At Cloud.” And John Scalzi took the whole thing down in one masterful tweet: “In fact, no self-respecting adult should give a shit what anyone else thinks about the entertainment they like.”

But there was one particular piece of this willfully ignorant, laughably hateful dreck that jumped out at me:

And yes, I know Persepolis started as a graphic novel – and very good it is too. But it’s an exception to the general rule that if you need to shave, you should be reading books where you have to make the pictures in your own head.

Really? Are we still, in 2016, seriously considering the question of whether comics and graphics novels are a serious form of literary art?

No. We’re not.

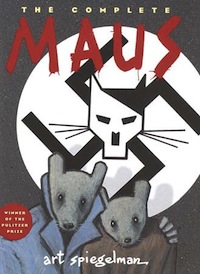

And Maus is very, very far from the only example of the comics form to earn and deserve respect. I have a memo for you, not just from 1992 and Maus, but from Fun Home. American Splendor. Love & Rockets. Blankets. Ghost World. Sandman. Watchmen. Why I Hate Saturn. Saga. Black Hole. Safe Area Gorazde. Barefoot Gen. Diary of a Teenage Girl. A Contract with God. American Born Chinese. Jimmy Corrigan. One Hundred Demons. Stuck Rubber Baby. My New York Diary. Akira. And yes, Persepolis, which you so casually dismissed as a fluke, an exception to the rule that you made up. Hell, I have a memo for you from Winsor McCay, from Little Nemo, from the year 1905.

There was a time when comics were considered silly and childish, and artists and fans had to fight for critical recognition. But that time is long past. That time is so far in the past, it’s old enough to drink. The list of counter-examples is so long, you could spend a lifetime reading nothing else and still not make a dent. Comics and graphic novels have had widespread critical recognition for decades. Maus won the Pulitzer Prize in 19-freaking-92.

So when you start rambling about how childish comics are, you’re not making comics look foolish. You’re making yourself look foolish. You aren’t just undercutting your opinions about comics or pop culture — you’re undercutting your opinions about culture, period. You’re making yourself look willfully ignorant, willfully out-of-date, unwilling to consider the possibility that your personal aesthetic tastes do not constitute a substantive social critique. And you’re not going to be taken seriously by anyone other than the rest of the Old Men Cloud-Yelling Society.