Discretion advised if graphic details of this subject upset you.

Somewhere or other, you’ve probably read the last post on this blog by now. Other versions of Maria Marcello‘s article ‘I Was Raped At Oxford University. Police Pressured Me Into Dropping Charges‘ have appeared at the Guardian, the Independent, the Daily Mail, the Tab, the Huffington Post and openDemocracy – the fact it’s the first thing she’s ever written is why you should follow her and why I’m privileged to be her editor. (It’s also why if you’re looking for one, you should hire me. Just saying.)

In the follow-up she published today, Marcello dissects what users at the Mail told her. Among other things, many fixated on her assumed inability to prove she was raped after falling asleep drunk.

I would ask this lady[:] Just what does she know about the event?

If you are so drunk that you have lost your memory or passed out how can you remember if you consented or not?

What evidence can she provide that she said ‘no’ to the main she claimed raped her?

How do you know you were raped if you don’t remember the night? In the period between being put to sleep and waking up with a man next to you, consensual sex could have been initiated, due to the heavy state of intoxication.

If you’re drunk and passed out, then who knows what happened? She could have dreamed the whole thing!

There would little to no evidence to bring a successful prosecution in this case. No DNA, no witnesses, no other evidence apart from a statement from someone who was so drunk they were passed out at the time with only a dim memory as their evidence.

In other words, her assault was just another case of ‘he-said-she-said college rape‘ where nothing could be proved.

As she notes in the sequel, the point of the original post was how much she could prove.

According to the Crown Prosecution Service and the Sexual Offences Act, extreme inebriation makes consent impossible. To prove her attacker raped her, Marcello had to establish a) that she was in such a state and b) that he had sex with her. What evidence did she – or rather, since I was with her at the time, we – have?

Well:

- We had Marcello’s word, mine and up to three other people’s that she was so drunk she had to be helped to bed (i.e. couldn’t walk unassisted).

- We had photos and several minutes of close-up video footage taken of her on the floor, unable to speak coherently and obviously extremely drunk.

- We may also have had forensic evidence of how much alcohol she’d consumed had police physicians examined her. (The CPS advises they present this sort of evidence to courts in rape trials.)

- We had Marcello’s word that she woke up while her attacker was having sex with her.

- We had the word of guests who believed this was about to occur when they left.

- We had the rapist’s statement witnessed by half a dozen people over dinner that he’d had sex with her, and possibly other statements to this effect.

- We had bruises on her upper thighs and her statement she had difficulty walking, which police physicians would have confirmed had they examined her.

- We had several used condoms which were presented to police.

- We had clothes and bedsheets covered in forensics which were presented to police.

This was the case a police official informed she didn’t have once they’d got her upset and alone, before making her decide on the spot whether to press charges. The pretext for making others leave the room, gut wrenchingly, was that she not be coerced out of doing so.

Says Marcello of the official:

She said she got called to investigate a number of rape reports each day and her job involved deciding which of them it was worthwhile to pursue and which it wasn’t. In her opinion, as she made clear from the start, mine fell into the latter category.

I have to wonder: if this wasn’t a case worth pursuing, what was? I’m not a lawyer, but my guess has always been that if she’d been allowed to speak to one before making her choice, they’d have told her it was stronger than average. Even without the forensics, it should have been enough for her college to expel the undergrad who raped her – if a student’s shown to have broken the law any other way, they don’t have to lose a court case before there are consequences.

The received wisdom about rape, especially where alcohol’s involved, is that it’s impossible to prove – a matter by definition of one person’s word against another’s. Since that day in Maria Marcello’s kitchen, I’d always assumed her case must be exceptionally good.

When Stephanie Zvan said this, as so often when I read her, my assumptions changed.

This is what drunken “he said-she said” college rape usually looks like. https://t.co/u6hS2sf0p8

— Stephanie Zvan (@szvan) August 29, 2014

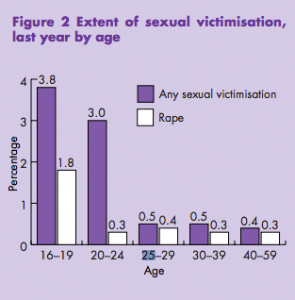

We know victims of sexual assault skew young. According to Britain’s Home Office, women aged 16-19 are at the highest risk of sexual victimisation, closely followed by those aged 20-24, and are four and a half times as likely as the next hardest hit age group to experience rape. (Marcello had just turned 20 at the time of her attack.) In other words, university-age women are the most raped demographic.

‘I’ve heard lots of stories similar to mine’, Marcello writes, ‘from people assaulted [at university].’ All factors suggest the reality we’re looking at is a very high number of rapes that share the broad outline of hers: heavy social drinking, a vulnerable or unconscious woman and a man who ‘took advantage’.

She had, I take it you’ll agree from the list above, a large amount of evidence both that she too drunk to consent and that her attacker had sex with her. But how much more was it than the average woman in her situation has?

Hours afterwards and with law enforcement’s tools, it’s not that hard to prove two people had sex – or at least, that someone with a penis had sex with somebody else in one of the ways the law requires for rape. Often seminal fluid can be found, either in used contraceptives or the when victim is examined. Often there are physical signs they were penetrated, including internal injuries. Often there are external marks left on them or forensics at the scene that point to sex. Sometimes the attacker thinks they did nothing wrong and <i>tells people</i> it happened, in person or by other (e.g. online) means. Sometimes they’re interrupted in the act, whether or not the witness views it as assault.

Many women in Marcello’s situation, I’d guess, have at least some such evidence.

Proving the absence of of consent can be more complex, but it doesn’t need to be when someone’s so drunk they can’t walk, talk or consent to sex. The video footage we had always struck me as an exceptional clincher, but then drunk photos and videos often appear on students’ social media accounts. Even when drunk victims aren’t filmed, they may be seen collapsing or needing help by far more people than a handful in their room – by crowds at a college party, for example. They may be assaulted after receiving first aid, being admonished by bouncers or no longer being served by bar stuff – all evidence of drunkenness. They may still be suffering symptoms of severe intoxication the next day, or have signs of it in their system police physicians can record.

Many women in Marcello’s situation, I’d guess, have at least some such evidence.

It’s still true, of course, that proving rape isn’t quite as straightforward as proving a crime where issues like consent aren’t involved. But it’s not true drunken college rapes are simply a case of he-said-she-said: on the contrary, extreme inebriation where demonstrable makes the absence of consent much more clear-cut.

Writes Marcello:

There would be more convictions if the police process didn’t pressure women with viable evidence to drop their reports. In 2012–13, official treatment of victims like me meant only 15 percent of rapes recorded by the police even went to court.

According to a report at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, official treatment of victims like her means evidence of vulnerability that should guarantee conviction – including drunkenness as well as things like disabilities – is routinely used precisely to dismiss reports, stop charges being pressed and get rapists off.

The best way to convict more is to stop telling victims with a strong case that they have no evidence.