‘I don’t really understand what biphobia is,’ a partner told me once. It was, he felt, a useless word. ‘If you’re a male bisexual, you’re normal except attracted to guys. The only people who object are homophobes.’ Like so many gay men, he thought the bi label was a way of clinging to a comfortable life, one foot in the straight camp for appearances’ sake. ‘You seriously think it’s harder to come out as bi?’ he asked when I said it had been for me. ‘Then you have no idea what you’re talking about.’ (‘To say it’s worse for bi people,’ he added later on, ‘I just found ignorant.’)

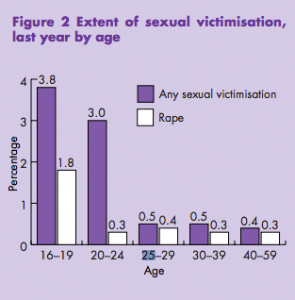

In the US, a quarter more bi men than gay men live in poverty, while fifty percent more abuse alcohol and contemplate suicide. Three times as many bi women as lesbians are raped, a third more abused by partners, two thirds more severely beaten by them. (Their numbers are also far worse than straight women’s.) Bi men are sexually assaulted more than gay men are and abused by their partners fifty percent more. Police attack three times as many bisexuals as monosexuals, and health workers place bi patients at risk of undiagnosed STIs by asking about their activities with one sex and not the other.

I could have offered statistics like those about our comfier, more normal lives. Instead I talked about my own. When the other guy informed people he was gay, how many told him he was lying or in denial? How many other gay men said he was untrustworthy and spread diseases? How many people said he should make up his mind, or wasn’t really gay? That he was misleading partners and making things more difficult for real gay people? How many kept calling him bi, despite him saying he wasn’t? ‘Wait,’ he replied. ‘Your point is that people don’t believe you’re bisexual? Why do they have to?’

If he wanted to understand biphobia, I said, he only had to listen to himself—but he insisted people not understanding something didn’t mean they were bigoted. ‘Instead of blaming them and calling them biphobic, it’s important to educate them. When the reaction is aggressive and defensive, of course people start to form their own weird opinions. You think every time someone makes a stupid comment about gays, I should just freak out? How is that supposed to help? It won’t change their mind. I’d rather stay put and explain. If you don’t have any patience, don’t moan about people not getting it!’

It’s conceivable people who disparage bisexuals should be able to reason for themselves, but cis gay men regularly tell LBTs to pipe down and be more polite, that they didn’t get where they are today with confrontation, anger or entitlement; that we won’t make strides of our own till we accept we owe people an education who demean and degrade us nonstop. Forget Stonewall and who was there, that bi people threw bricks at police while homophiles told them and poor, black, brown, Jewish and trans queers to be quiet: abandoning self-respect was what Pride was all about.

Anger has changed my mind plenty of times, and I know mine has changed other people’s—alienating those you care about, it transpires, is a good incentive to adjust how you act—but when at-risk groups are told we need to school people who treat us badly, it’s always as if there’s no overlap. Bi people need to educate gay and straight people, not to scream at them. Trans people need to educate cis people, not to bully them. Black people need to educate white people, not to frighten them. People with disabilities need to educate people without, not throw a fit. It’s always one or the other.

I told the other bloke what people like me tell people like him, that it isn’t marginalised people’s duty to be teachers—but I think there’s another issue here. Lots of us want to be educators, and we know the difference between being listened to and being talked over, between salient, responsive questions and irrelevant ones—between privileged people who know where their knowledge ends and those who speak like they know more than us. We know the ones who value our input are the ones who know we don’t owe it to them. We know the ones who order us to school them are never the ones who want to learn.

Here’s my experience: when someone I’ve called ignorant demands I educate them, they don’t want me to be patient—they want me to have infinite patience, to listen to them affably, without anger, however they behave, and to treat anything they say as valuable. They want me to teach them what I know, but not to act like I know more than them. They don’t want me to assert any control of the discussion, to set limits on what I’m willing to explain, on where and when and for how long, or to impose any kind of boundaries. When they tell me to educate them, what they mean is ‘Shut up, I’m talking.’

Professional educators—teachers, lecturers, instructors, sports coaches, health experts—are authorities in their field who expect to be listened to, not talked over. Good educators expect students to learn on their own instead of being spoonfed; they reward some contributions more than others and impose boundaries on how their students act. Bad educators display infinite patience; good ones are patient but know where to draw the line, as well as how and when to get angry. Good ones nurture relationships with their students but allow bad attitudes to harm them.

When I request input from someone with a background I don’t share—legal advice, tech help, perspective from a black or trans colleague—that’s the kind of relationship I want. When people ask for my input, I sense it’s what they want as well. When I needed an education in the past, getting kicked round the room for being ignorant was a pretty effective one—but when people who’ve just insulted me tell me I’m obliged to educate them, I don’t think an educator is what they want at all. I think what they want is an enabler and a doormat, and I have better things to do than supply one.

And that partner of mine? We didn’t last.