Take Back the Night

(A little music to set the mood, maestro.)

Scientists Play With Their Food

It’s that time of the year when we’ve probably filled ourselves with more food than we could hold. Before the diet begins, let’s hold one last feast, courtesy of science.

Scientists studying food have made our harvests more bountiful, our turkeys bigger, and are discovering new foods for us to serve up. They’ll make it possible to eat green, eat well, and eat healthy. Not bad results for a bunch of guys in lab coats playing with food, eh?

Wired Science often has delightful articles on food-related science. I’ve chosen out appetizers from some of their recent offerings for your dining pleasure. Be sure to click through for the full meal. Bon appétit!

It’s appetizing news for anyone who’s ever wanted the savory taste of meats and cheeses without actually having to eat them: chemists have identified molecular mechanisms underlying the sensation of umami, also known as the fifth taste.

The much-loved but historically unappreciated taste is produced by two interacting sets of molecules, each of which is needed to trigger cellular receptors on a tongue’s surface.

“This opens the door to designing better, more potent and more selective umami enhancers,” said Xiaodong Li, a chemist at San Diego-based food-additive company Senomyx. Li co-authored the study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Four other basic tastes — bitter, sweet, salty and sour — were identified 2,400 years ago by the Greek philosopher Democritus, and became central to the western gastronomic canon.

In the late 19th century, French chef and veal-stock inventor Auguste Escoffier suggested that a fifth taste was responsible for his mouth-watering brew. Though Escoffier’s dishes were popular, his theories were dismissed until 1908, when Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda showed that an amino acid called glutamate underlies the taste of a hearty variety of seaweed soup.

In honor of Ikeda, the taste was dubbed umami, the Japanese word for delicious. It took another 80 years for umami to be recognized by science as comparable to the other four tastes.

Human hair could be used instead of chemical fertilizers for some plants like lettuce, new research in a horticultural journal suggests.

The hair, which is manufactured into cubes from barbershop and hair-salon waste, provides nitrogen for plants as it decomposes, just as natural-gas-derived sources like ammonia do.

“Once the degradation and mineralization of hair waste starts, it can provide sufficient nutrients to container-grown plants and ensure similar yields to those obtained with the commonly used fertilizers in horticulture,” said horticulturalist Vlatcho Zheljazkov of Mississippi State University.

All plants need nitrogen to grow. These plants form the basis of the proteins which eventually make their way into our bodies either directly through the consumption either of the plants themselves or of animals raised on plants. Our bodies turn those proteins into all sorts of useful things — like muscles — and some less useful things, like hair. In fact, studies carried out in the 1960s found that human hair contains about 15 percent nitrogen [pdf].

Ask America’s foremost molecular gastronomist about the Willy Wonka comparisons, and Homaro Cantu will insist that he’s just an average guy who likes cheeseburgers. But it’s not cheeseburgers that have earned the Chicago chef fame: it’s dishes prepared with industrial lasers, inkjet printers and liquid nitrogen.

Look beneath the technical sophistication, though, and Cantu’s kitchen pyrotechnics are revealed as explorations of possible answers to a very simple question: What is food? And if the cuisine at Moto, his “molecular tasting lab,” can be described as postmodern, Cantu himself has little time for gastro-academic posing. He’s driven by a techno-utopian vision of decentralized food in which the world’s ever-growing appetites are met by a radical transformation of agriculture itself — and it all begins in our kitchens.

“Make enough food for everyone. That’s the end game,” says Cantu. “And to get there, we have to start thinking a little crazier about what food is.”

Saltwater-loving plants could open up half a million square miles of previously unusable territory for energy crops, helping settle the heated food-versus-fuel debate, which nearly derailed biofuel progress last year.

By increasing the world’s irrigated acreage by 50 percent, saltwater crops could provide a no-guilt source of biomass for alt fuel makers and tone down the rhetoric of U.N. officials worried about food prices, one of whom called the conversion of arable land to biofuel crops “a crime against humanity.”

While growing crops in saltwater has been on the fringes of horticulture for decades, the new demand for alternative energy has pushed the idea onto the pages of the nation’s most prestigious scientific journal and drawn the attention of NASA scientists.

Citing the work of Robert Glenn, a plant biologist at the University of Arizona, two biologists argue in this week’s Science that “the increasing demand for agricultural products and the spread of salinity now make this concept worth serious consideration and investment.”

Genetically engineered peanuts may help fight the most common cause of fatal allergic reactions to food in the United States. While the research is unlikely to result in the creation of completely allergen-free peanuts, it could result in fewer outbreaks and even fewer deaths.

For years now, gov

ernment scientists have been testing ordinary peanuts in the hope of finding one that cannot cause the deadly allergic reactions which kill more than 50 Americans every year. But nature may not be able to provide an answer.

Horticulture expert Peggy Ozias-Akins at the University of Georgia in Tifton is taking a different tack by using genetic engineering to grow hypoallergenic peanuts.

Your corn is sweeter, your potatoes are starchier and your turkey is much, much bigger than the foods that sat on your grandparents’ Thanksgiving dinner table.

Most everything on your plate has undergone tremendous genetic change under the intense selective pressures of industrial farming. Pilgrims and American Indians ate foods called corn and turkey, but the actual organisms they consumed didn’t look or taste much at all like our modern variants do.

In fact, just about every crop and animal that humans eat has experienced some consequential change in its DNA, but human expectations have changed right along with them. Thus, even though corn might be sweeter now, modern people don’t necessarily savor it any more than their ancestors did.

“Americans eat a pound of sugar every two-and-a-half days. The average amount of sugar consumed by an Englishman in the 1700s was about a pound a year,” said food historian Kathleen Curtin of Plimoth Plantation, a historical site that recreates the 17th-century colony. “If you haven’t had a candy bar, your taste buds aren’t jaded, and your apple tastes sweet.”

The traditional Thanksgiving dinner reflects the enormous amount of change that foods and the food systems that produce them have undergone, particularly over the last 50 years. Nearly all varieties of crops have experienced large genetic changes as big agriculture companies hacked their DNA to provide greater hardiness and greater yields. The average pig, turkey, cow and chicken have gotten larger at an astounding rate, and they grow with unprecedented speed. A modern turkey can mature to a given weight at twice the pace of its predecessors.

Unsung Women of Science

The history of science, you may have noticed, is dominated by men. When we’re pulling names of famous scientists from the tops of our heads, the vast majority are male: Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein. If women come up at all, it’s a paltry few: Madame Curie, of course. Perhaps Vera Rubin, Dian Fossey, Mary Leakey or Rosalind Franklin, if you know your science well. But you’d be forgiven for thinking that women were vanishing rare in science before the mid-to-late 20th Century.

But delve deeper, and you find women there from the very beginning. Their work went unnoticed, unappreciated, or usurped by a male-dominated world, yet they worked on, performing experiments, making discoveries, fleshing out theories. You never realize how much women have contributed to science until you look.

While I was reading E = mc²: A Biography of the World’s Most Famous Equation, I stumbled across three extraordinary women who contributed to Einstein’s revolutionary physics. They prove beyond a reasonable doubt that science isn’t just for the men.

History knows her as Voltaire’s mistress, conveniently forgetting that she more than any other person was responsible for bringing the gospel of Newton to passionately Cartesian France.

Born in 1706, she lived in a time when women were expected to become nothing much more than wives, mothers and mistresses. Education for women was limited, but her father, seeing her intelligence, had her privately tutored. He also gave her fencing lessons to help her develop graceful movement – lessons which she later put to good use fending off annoying suitors. Not many men were willing to pursue an unwanted relationship with a woman who could best them with the foil.

She married the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet, whom she knew would be away on military campaigns much of the time and thus leave her to her own devices, which consisted of a series of liasons that not only fed her need for male companionship, but furthered her scientific education. One lover, the Duc de Richelieu, encouraged her to learn higher mathematics. She became fascinated by Newton in her 20s, and spent the rest of her life bringing his elegant theories of gravity to France.

She met and fell in love with Voltaire after he returned from exile in England. They set about turning her husband’s disused country chateau into their own laboratory, stocking it with over 21,000 books – far more than some universities contained. She tested Newton’s theories in the great hall, swinging wooden balls from the rafters. Together, in 1738, she and Voltaire wrote Elements of Newton’s Philosophy, although “together” may be the wrong word. Voltaire said of their collaboration, “She dictated and I wrote.” His name appears as the sole author, but the book was illustrated with an image of Emilie shining Newton’s knowledge on Voltaire’s hand. The book brought Newton to France, explaining his discoveries in light, optics, and astronomy for a wide audience. It was the beginning of the end for Descartes as France’s premier scientific theorist.

Emilie wrote her own book, The Foundations of Physics, which combined the theories of Descartes, Leibniz, and Newton into an elegant whole. The book, published anonymously, resolved previously intractable problems in describing force and movement.

Her most prestigious work was undertaken at the end of her life. She translated Newton’s Principia into French from the original Latin. Her translation, which is not merely a rendition of Newton’s text but also translated Newton’s geometry into the new algebra then current on the Continent, converted the complex mathematics into prose, and summarized recent research and experimental confirmations of Newton’s work. Her translation is still the standard translation of Principia into French.

As she was writing the book, she discovered she was pregnant – a virtual death sentence for a forty-two year-old woman in that age. She pushed herself to work eighteen-hour days, and finished the book on September 1st, 1749. Three days later, she went into labor; less than a week later, she died from either infection or embolism, leaving Voltaire distraught.

Aside from her books, her most astounding contribution to physics was the realization that Newton was wrong. She discovered the experimental results of William s’Gravesande, who had discovered by dropping brass balls into a clay floor that something moving twice as fast will bury itself twice as deep – energy doesn’t merely equal mass times velocity, but mass times velocity squared. With those results in hand, she was able to prove that Leibniz had been right: E ∝ mv². Scientists now started thinking in squares.

I think you know where that led.

Further reading:

Wikipedia entry

Physicsworld: “The Genius Without a Beard”

Born in 1878, Lise Meitner cracked a lot of glass ceilings and should have won a Nobel Prize. She discovered nuclear fission, which earned her the unwanted title of “Mother of the Atomic Bomb.”

She studied physics at the University of Berlin. At that time, women in science, especially the hard sciences, was nearly unheard of – she had to get permission to attend classes. Max Planck didn’t believe it was right or natural for women to do more than become housewives and mothers, but he let Lise in – and she did so well she ended up becoming his research assistant.

After university, she and her research partner Otto Hahn moved to the new radiation research unit at the Kaiser-Willhelm Institute. Lise came as his “unpaid guest” – women could not be official employees of the Institute. She did the lion’s share of the work, while Hahn’s name ended up as senior author on all of their papers, and she ended up with only a copy of the award their work won.

Her fortunes changed after WWI, when she became Germany’s first woman professor. She became a full professor of physics at the University of Berlin, where she continued her studies of radiation, atomic theory, and quantum mechanics. But her Jewish heritage caught up with her: she was forced to flee Berlin, leaving Hahn and all of her work behind. She ended up in Stockholm, Sweden, where she discovered that mass is lost when a nucleus splits, released as energy. Einstein’s E = mc² told her how much energy would be released: using his theory, she was able to predict that a chain reaction could result. She wrote to Hahn to share her theory: he did the experiments and published the results – without mentioning her name. Later, he convinced himself that his work alone had resulted in the discover of nuclear fission, for which he won the Nobel Prize.

Franklin Roosevelt invited Lise to work at Los Alamos, where the first atomic bomb was being developed. Lise refused. She would have no hand in using her discovery to kill.

Later in life, she finally received the honors she deserved. Appropriately enough, she received the Max Planck Medal. She also won the Enrico Fermi Award and was elected to the Swedish Academy of Science. Only two other women had ever earned a position at the Academy before her. Long after her death, the 109th element, meitnerium, was named for her.

The inscription on her headstone was written by her nephew, Otto Frisch. It sums her up perfectly: “Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity.”

Further reading:

Neatorama, “Lise Meitner: Mother of the Atomic Bomb”

Born in 1900, Cecilia ended up coming to America from England for the freedom to be a woman and a scientist.

She completed her early education at Cambridge, but earned no degree – degrees weren’t awarded to women at that time. Fortunately, she met Harlow Shapley, director of the Harvard College Observatory, and realized that Harvard was far more open to women. She crossed the pond and, with Shapley’s encouragement, wrote her doctoral dissertation on “Stellar Atmospheres, A Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars.” It marked a huge turning point for women in science: before then, women didn’t do PhD’s, but more than that, her dissertation was very nearly a bombshell:

Astronomer Otto Struve characterized it as “undoubtedly the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy”. By applying the ionization theory developed by Indian physicist Megh Nad Saha she was able to accurately relate the spectral classes of stars to their actual temperatures. She showed that the great variation in stellar absorption lines was due to differing amounts of ionization that occurred at different temperatures, and not due to the different abundances of elements. She correctly suggested that silicon, carbon, and other common metals seen in the sun were found in about the same relative amounts as on earth but the helium and particularly hydrogen were vastly more abundant (by about a factor of one million in the case of hydrogen). The thesis thus established that hydrogen was the overwhelming constituent of the stars. When her thesis was reviewed, she was dissuaded by Henry Norris Russell from concluding that the composition of the sun is different from the earth, which was the accepted wisdom at the time. However Russell changed his mind four years later when other evidence emerged.

Until Cecilia’s work, no one had considered that the sun might be mostly hydrogen and helium. The realization to the contrary revolutionized the way we think of stars – after folks started accepting the evidence.

She spent the rest of her life studying stars and teaching astronomy students. Her work on high-luminosity stars, along with the surveys she and her husband did on stars brighter than the tenth magnitude – a staggering 3,250,000 or so observations – helped astrophysicists understand stellar evolution.

Further reading:

Notable American Unitarians, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin: Astronomer and Astrophysicist

Many women have now followed the trails these extraordinary females blazed. Science is indebted to their discoveries. It’s never been just a man’s world, as these three women and countless others prove. Science wouldn’t be the same without them. That being so, it’s time to start singing their praises.

Digging in the past.

Archaeology is one of the most fascinating branches of science. Uncovering our buried history helps us make sense of who we are, how we thought, and can help us understand why civilizations rise and fall. Ancient cultures were beautiful, brutal, and just plain interesting.

There have been several recent discoveries that reveal origins more ancient than we expected, potentially solve some longstanding mysteries, and give us unanticipated glimpses into our ancestors’ physiology. Let’s dig, shall we?

The 4,300-year-old monument is believed to be the tomb of Queen Sesheshet, the mother of Pharaoh Teti, the founder ancient Egypt’s 6th dynasty.

Once nearly five stories tall, the pyramid—or at least what remains of it—lay beneath 23 feet (7 meters) of sand.

The discovery is the third known subsidiary, or satellite, pyramid to the tomb of Teti. It’s also the second pyramid found this year in Saqqara, an ancient royal burial complex near current-day Cairo.

[snip]

Starting from the 4th dynasty (2616 to 2494 B.C.), pharaohs often built pyramids for their wives and mothers.

“Mothers were revered in ancient Egypt,” said Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, who was not involved in the discovery.

“Building pyramids for one’s mother in her dead state … was fairly emphasized in the whole vision of kingship that the ancient Egyptians had,” Ikram said.

“That was something that was instituted during [a pharaoh’s] lifetime and was a very public way of expressing his debt to her, his connection to her, and her importance in Egypt politically and as a symbol for kingship.”

The first excavation of Stonehenge in more than 40 years has uncovered evidence that the stone circle drew ailing pilgrims from around Europe for what they believed to be its healing properties, archaeologists said Monday.

DNA Identifies Copernicus’s Remains

Researchers said Thursday they have identified the remains of Nicolaus Copernicus by comparing DNA from a skeleton and hair retrieved from one of the 16th-century astronomer’s books. The findings could put an end to centuries of speculation about the exact resting spot of Copernicus, a priest and astronomer whose theories identified the Sun, not the Earth, as the center of the universe.

Polish archaeologist Jerzy Gassowski told a news conference that forensic facial reconstruction of the skull, missing the lower jaw, his team found in 2005 buried in a Roman Catholic Cathedral in Frombork, Poland, bears striking resemblance to existing portraits of Copernicus.

The reconstruction shows a broken nose and other features that resemble a self-portrait of Copernicus, and the skull bears a cut mark above the left eye that corresponds with a scar shown in the painting.

Moreover, the skull belonged to a man aged around 70 — Copernicus’s age when he died in 1543.

In 1706, Paul Lucas, traveling in southwest Turkey on a mission for the court of Louis XIV, came upon the mountaintop ruins of Sagalassos. The first Westerner to see the site, Lucas wrote that he seemed to be confronted with remains of several cities inhabited by fairies. Later, during the mid-nineteenth century, William Hamilton described it as the best preserved ancient city he had ever seen. Toward the end of that century, Sagalassos and its theater became famous among students of classical antiquity. Yet large scale excavations along the west coast at sites like Ephesos and Pergamon, attracted all the attention. Gradually Sagalassos was forgotten…until a British-Belgian team led by Stephen Mitchell started surveying the site in 1985.

Since 1990, Sagalassos has become a large-scale, interdisciplinary excavation of the Catholic University of Leuven, directed by Marc Waelkens. We are now exposing the monumental city center and have completed, or nearly completed, four major restoration projects there. We’ve also undertaken an intensive urban and geophysical survey, excavations in the domestic and industrial areas, and an intensive survey of its vast territory. Whereas the former document a thousand years of occupation, from Alexander the Great to the seventh century, the latter has established the changing settlement patterns, the vegetation history and farming practices, the landscape formation and climatic changes during the last 10,000 years.

British archaeologists have unearthed an ancient skull carrying a startling surprise _ an unusually well-preserved brain. Scientists said Friday that the mass of gray matter was more than 2,000 years old _ the oldest ever discovered in Britain. One expert unconnected with the find called it “a real freak of preservation.”

The skull was severed from its owner sometime before the Roman invasion of Britain and found in a muddy pit during a dig at the University of York in northern England this fall, according to Richard Hall, a director of York Archaeological Trust.

Finds officer Rachel Cubbitt realized the skull might contain a brain when she felt something move inside the cranium as she was cleaning it, Hall said. She looked through the skull’s base and spotted an unusual yellow substance inside. Scans at York Hospital confirmed the presence of brain tissue.

Space Through Hubble’s Eyes

The Challenger disaster delayed Hubble’s scheduled launch in 1986. Discovery finally took the telescope into orbit in 1990. Then the first images came back, and showed a nearly fatal flaw with the primary mirror. What a difference 2.3 micrometers makes! The flaw meant that Hubble had no problem with bright objects, but couldn’t see faint ones in enough detail to perform its mission. So, of course, scientists designed spectacles, and Hubble took a clear, deep look into space. It’s appropriate that it was launched on a shuttle named Discovery, because its discoveries have been truly incredible.

The best available information indicates that the age of the universe is 13.7 billion years. Hubble has helped to measure the age of the universe using two different methods. The first method involves measuring the speeds and distances of galaxies. Because all of the galaxies in the universe are generally moving apart, we infer that they must all have been much closer together sometime in the past. Knowing the current speeds and distances to galaxies, coupled with the rate at which the universe is accelerating, allows us to calculate how long it took for them to reach their current locations. The answer is about 14 billion years. The second method involves measuring the ages of the oldest star clusters [link]. Globular star clusters orbiting our Milky Way are the oldest objects we have found and a detailed analysis of the stars they contain tells us that they formed about 13 billion years ago. The good agreement between these two very different methods is an encouraging sign that we are honing in on the universe’s true age.

Called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, the view represents the deepest portrait of the visible universe ever achieved by humankind. The snapshot reveals the first galaxies to emerge from the so-called “dark ages,” the time shortly after the big bang when the first stars reheated the cold, dark universe. The new image should offer new insights into what types of objects reheated the universe long ago.

A new image from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope shows the colorful “last hurrah” of a star like our sun. The picture was taken on Feb. 6, 2007, by Hubble’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2, which was designed and built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. The star is ending its life by casting off its outer layers of gas, which formed a cocoon around the star’s remaining core. Ultraviolet light from the dying star makes the material glow. The burned-out star, called a white dwarf, is the white dot in the center. Our sun will eventually burn out and shroud itself with stellar debris, but not for another 5 billion years.

Astronomers have long puzzled over why a small, nearby, isolated galaxy is pumping out new stars faster than any galaxy in our local neighborhood. Now NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has helped astronomers solve the mystery of the loner starburst galaxy, called NGC 1569, by showing that it is one and a half times farther away than astronomers thought. The extra distance places the galaxy in the middle of a group of about 10 galaxies centered on the spiral galaxy IC 342. Gravitational interactions among the group’s galaxies may be compressing gas in NGC 1569 and igniting the star-birthing frenzy. “Now the starburst activity seen in NGC 1569 makes sense, because the galaxy is probably interacting with other galaxies in the group,” said the study’s leader, Alessandra Aloisi of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md., and the European Space Agency. “Those interactions are probably fueling the star birth.” The farther distance not only means that the galaxy is intrinsically brighter, but also that it is producing stars two times faster than first thought. The galaxy is forming stars at a rate more than 100 times higher than in the Milky Way. This high star-formation rate has been almost continuous for the past 100 million years. Discovered by William Herschel in 1788, NGC 1569 is home to three of the most massive star clusters ever discovered in the local universe. Each cluster contains more than a million stars.

Hubble peered into a small portion of the Tarantula nebula near the star cluster NGC 2074. The region is a firestorm of raw stellar creation, perhaps triggered by a nearby supernova explosion. It lies about 170,000 light-years away and is one of the most active star-forming regions in our local group of galaxies. The image reveals dramatic ridges and valleys of dust, serpent-head “pillars of creation,” and gaseous filaments glowing fiercely under torrential ultraviolet radiation. The region is on the edge of a dark molecular cloud that is an incubator for the birth of new stars. The high-energy radiation blazing out from clusters of hot young stars is sculpting the wall of the nebula by slowly eroding it away. Another young cluster may be hidden beneath a circle of brilliant blue gas.

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has discovered carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a planet orbiting another star. This breakthrough is an important step toward finding chemical biotracers of extraterrestrial life. The Jupiter-sized planet, called HD 189733b, is too hot for life. But the Hubble observations are a proof-of-concept demonstration that the basic chemistry for life can be measured on planets orbiting other stars. Organic compounds also can be a by-product of life processes and their detection on an Earthlike planet someday may provide the first evidence of life beyond our planet. Previous observations of HD 189733b by Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope found water vapor. Earlier this year, Hubble found methane in the planet’s atmosphere. “Hubble was conceived primarily for observations of the distant universe, yet it is opening a new era of astrophysics and comparative planetary science,” said Eric Smith, Hubble Space Telescope program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “These atmospheric studies will begin to determine the compositions and chemical processes operating on distant worlds orbiting other stars. The future for this newly opened frontier of science is extremely promising as we expect to discover many more molecules in exoplanet atmospheres.”

There is too much. I have merely summed up, not ‘splained. Go. Look. Marvel.

A Little Science With Your Fiction

Everyone knows that what you read in a fantasy novel or see in a “science” fiction movie isn’t real science, but that doesn’t stop real scientists from playing “what if?” Popular fiction is an excellent vehicle for transporting science into minds that might otherwise never have bothered. And if you’ve got someone on your shopping list who claims science isn’t interesting but loves science-inspired entertainment, one of these books may be an ideal way to show them that real science isn’t boring.

And if that’s not enough, there’s also Beyond Star Trek, in which Krauss takes on the paranormal and destroys the idea that a huge-ass spaceship could hover over the White House without crushing it.

You can even read a few excerpts over at SciAm.com. You can tell by the excerpt titles that the whole book is snarky good science fun.

Science of Discworld I, II and III by Terry Pratchett et al.

It’s no secret that I’m a ginormous Terry Pratchett fan, and one of the singular delights in reading his books is the way quantum physics sneaks in to a world riding on the backs of four elephants standing on a turtle swimming through space. Who doesn’t giggle at the Trousers of Time? Or delight in L-Space? I haven’t had the chance to read these – I didn’t even know they existed until tonight – but the reviewers assure me the science within is teh awesome. Terry not only tells us the facts, but shows us how science discovers them – which is the single most important part of science, innit?

Sunday Sensational Science is over at Slobber and Spittle this week. Cujo359 has put together a fantastically beautiful article on clocks of all sorts, from the crudest clocks in stone to the most sensitive atomic models. I was grateful when he offered to let me filch it so that I could finish NaNo without trying to put together something non-hokey, and I’m thrilled with the result. We’ve got one of the best Sunday Science articles ever, and I finished this damned book.

Not bad!

Go. Enjoy. Wonder why the hell Dana can’t do anything half so good.

Muchos gracias, Cujo! Salud, mi amigo.

Mixing the science up with the opera

Lab coats on Broadway – aside from mad scientists, when have we ever seen such a thing? Science is seen as useful, practical, often beautiful, but hardly an inspiration for librettos.

But that’s changing.

Darwin’s getting an opera-oratorio. Genetic science inspired a chamber opera. And now, a physicist has a full-blown opera:

There are certain characters in science who stand out for their larger-than-science characteristics: Galileo and his conflicts with Papal authorities; Albert Einstein and his political dabblings and pacifist overtures; Richard Feynman and his safecracking, storytelling antics; Stephen Hawking and his ethereal brain trapped in a frozen body. Biographies, documentaries, films, and even plays have attempted to capture the essence of these giants (see QED, for example, the play starring Alan Alda as Feynman). But to my knowledge, none have had an opera produced in their likeness.

Enter Doctor Atomic, a look at the meaning behind the making of the atomic bomb from the perspective of its paterfamilias J. Robert Oppenheimer and his disparate struggles: with nature to reveal her secrets, with his conscious to ease his guilt. He also struggles with General Leslie R. Groves, the titular military head of the Manhattan Project, and with fellow physicist and future father of the H-Bomb, Edward Teller.

Fantastic, isn’t it? With this, science has a solid claim to high culture.

Have a listen to the Bhagavad Gita Chorus from Doctor Atomic:

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds” floated through Oppenheimer’s mind as he watched the first bomb burst at Trinity Site. It’s tremendous to see that moment captured in music.

Our own incisive regular, Cujo359, has an excellent post up on this opera and Oppenheimer’s life. And, just in case you’ve got an hour on your hands and want the backstory on the opera, I’ve included “Science and the Soul: J. Robert Oppenheimer and Doctor Atomic” for your viewing pleasure:

Celebrating San Francisco Opera’s world premiere of Doctor Atomic, this symposium brings together composer John Adams, director Peter Sellars, and UC Berkeley’s Marvin Cohen and Mark Richards to explore J. Robert Oppenheimer’s role in the creation of the first atomic bomb and examines the historical, scientific, and musical background of “Doctor Atomic.”

This isn’t science’s first foray into opera. In 2004, genetic science became the basis for a charming little chamber opera:

A fusion of music, art and science, inspired by contemporary genetic discovery and brought together in the style of a chamber opera, is to have its world premiere at Baltic, the Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead.

‘Hidden States’ is the result of a trans-Atlantic collaboration involving music scholars and visual artists from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. It will be performed publicly for the first time at Baltic on Friday 26 November.

The project is the first collaboration on a music theatre project between British composer Jonathan Owen Clark, formerly a lecturer in the International Centre for Music Studies at Newcastle University, and American opera specialist and librettist, David Moody, who is Assistant Director of the Opera Company of Philadelphia.

Conceived as a chamber opera for a small ensemble and baritone performed alongside specially-commissioned synchronised video projections, ‘Hidden States’ draws parallels between alchemy – the forerunner of modern chemistry – and contemporary genetic science.

In a sequence of five monologues, Paracelcus the alchemist – sung by baritone Paul Carey Jones – articulates his hopes and dreams for the creation of a living human being from inanimate matter.

Composer Jonathan Owen Clark said: ‘Collaboration between artists and scientists in the quest to explain some of the myths and mysteries of cutting edge science and its history is not a new idea, but in Hidden States the aim is to provide, in perhaps a new format, an account of certain key concepts in contemporary genomics and bioinformatics. These include sequencing and cloning, and how they fit within the broader themes of cultural, literary and scientific history.

Alas, YouTube has failed me here. But there were plans to turn “Hidden States” into a full opera, and with the success of Doctor Atomic, we might be seeing that happen very soon.

We’ll be celebrating Darwin’s 200th with Tristero’s glorious The Origin, which I’ve mentioned here in the cantina before:

After a year and a half of near-daily composing, I have finally finished The Origin, an opera-oratorio inspired by the life and works of Charles Darwin. It was a challenging, and very enjoyable, project and will premiere February 9, 2009 at the State University of New York, Oswego – that’s 3 days before Darwin’s 200th birthday!

The music is scored for Soprano, Baritone, chorus, orchestra, and the wonderful Eastern European female choir, Kitka. In addition, the brilliant filmmaker Bill Morrison – known for his work with Ridge Theater, Michael Gordon, and others – will be creating films and other visuals for the performance.

[snip]

The texts used in the Origin are taken entirely from the writings of Charles Darwin – with a brief cameo by his wife, Emma. They were compiled and arranged by poet Catherine Barnett and myself. Most of the words come from The Origin of Species; the so-called “transmutation notebooks;” Darwin’s autobiography; The Voyage of the Beagle; and his letters (you can find a huge selection of Darwin’s writings at this incredible site). My purpose was to celebrate Darwin’s thought and life in music, concentrating specifically on the writing and ideas in The Origin of Species.

So far, there’s only two clips up, but they show that this opera-oratorio is going to make Darwin proud.

Annie’s Memorial

Representations of Chaos

We science-lovers have always known that science has the kind of power, beauty and wonder than can inspire incredible works of art. Now, with science on Broadway, we can show the rest of the world what they’ve been missing.

(Special bonus points to anyone who figured out that this Sunday’s Sensational Science title is a paraphrase from Operatica. Free booze for life for anyone who convinces Operatica to do a concept album around science.)

A Cornucopia of Science

No, it’s not quite Thanksgiving yet, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have an abundance of extraordinary science to be thankful for. Here are just a few of the wonders spilling from our horn of plenty.

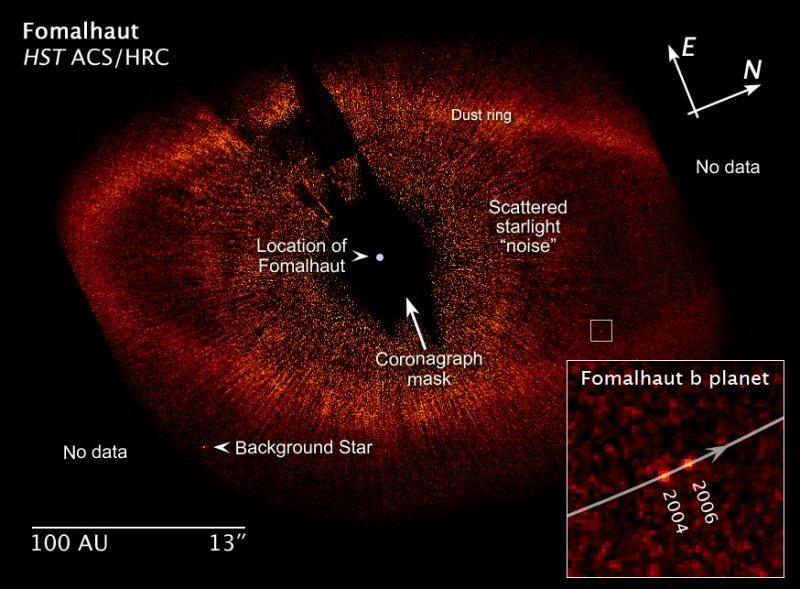

After an eight-year quest for images, a US astronomer using a camera aboard the Hubble space telescope has snapped the first picture of a planet outside our solar system.

Astronomer Paul Kalas captured the first visible-light images of a planet some 25 light years from our solar system using a camera mounted on the Hubble telescope.

Likely similar in mass to Jupiter, the planet is orbiting the star Fomalhaut in the southern constellation Piscus austrinus at a distance of about four times the distance between Neptune and our sun, said the study’s lead author Kalas, with the University of California, Berkeley.

The research appears in the November 14 online edition of the review Science.

The planet, dubbed Fomalhaut b, could have a system of rings similar in dimension to what Jupiter had in the past, before dust and debris joined together to form its four main moons.

(Image from Astronomy Picture of the Day)

And, as Phil Plait at the Bad Astronomy blog says, there’s more:

That image is the first to directly show two planets orbiting another star!

It’s a near-infrared image using the giant Gemini North 8 meter telescope. Like in the Hubble image, the star’s light has been blocked, allowing the two planets to be seen (labeled b and c).

The star is called HR 8799. It’s a bit more massive (1.5 times) and more luminous (5x) than the Sun, and lies about 130 light years from Earth. The planets in this picture orbit it at distances of 6 billion km (3.6 billion miles) and 10.5 billion km (6.3 billion miles). A third planet, not seen in this image but discovered later u

sing the Keck 10 meter telescope, orbits the star closer in at a distance of 3.8 billion km (2.3 billion miles).

So there it is. The first ever family portrait of a planetary system.

One thing that makes these particular planets a bit easier to find than usual is that they are young; HR 8799 and its children are only about 60 million years old. That means the planets are still glowing from the leftover heat of their formation, and that adds to their brightness. Eventually (in millions of years), as they cool, they will glow only by reflected light from the star, and be far harder to see. Fomalhaut b, in the Hubble image, is much older (200 million years), and glows only by reflected light from Fomalhaut. If it were much smaller or dimmer (or closer to the blinding light of the star), we wouldn’t have been able to see it at all.

These images were basically science fiction just a few years ago. Now they are fact. We have an optical picture of a planet orbiting another sun-like star, and a picture of two planets orbiting another star.

Wow. Just wow.

Wow, indeed.

Time to return to Earth, away from giant planets, and delve into the world of the tiny:

The Nanotech Antidote to Food Poisoning

This week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Bundle described special polymers that can remove toxins from the bloodstream. Doctors could inject the nano-medicine into gravely ill patients to protect them from damage caused by bacteria such as hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

Each of the stringy saviors, called PolyBAIT, is decorated with carbohydrates that act like barbs. Those little hooks can sn

ag bacterial poisons and then stick them to an immune system protein.

The protein and PolyBAIT disar

m each toxin molecule, and then drag them out of the bloodstream.

Bundle and others have been trying to deactivate parasite poisons for quite some time, but their earlier antidotes did not work well on animals.

Along with colleagues Pavel Kitov and Glen Armstrong, Bundle tested PolyBAIT on transgenic mice. When they gave a lethal dose of shiga toxin to their fuzzy research subjects, the new medication was able to save them.

Awesome.

We aren’t the only ones who hold elections, it appears:

Fish Choose Their Leaders by Consensus

Just after Americans have headed to the polls to elect their next president, a new report in the November 13th issue of Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, reveals how one species of fish picks its leaders: Most of the time they reach a consensus to go for the more attractive of two candidates.

“It turned out that stickleback fish preferred to follow larger over smaller leaders,” said Ashley

Ward of Sydney University. “Not only that, but they also preferred fat over thin, healthy over ill, and so on. The part that really caught our eye was that these preferences grew as the group size increased, through some kind of positive social feedback mechanism.”

“Their consensus arises through a simple rule,” said David Sumpter of Uppsala University. “Some fish spot the best choice early on, although others may make a mistake and go the wrong way. The remaining fish assess how many have gone in particular directions. If the number going in one direction outweighs those going the other way, then the undecided fish follow in the direction of the majority.”

Majority rules, even under the sea.

Could this explain why religious people see the world so differently from us?

Religion Alters Visual Perception

It might be clichéd to say that religious people see the world differently, but new research finds that Dutch Calvinists notice embedded visual patterns quicker than their atheist compatriots.

Culture has long been known to distort visual perception, says Bernhard Hommel, a psychologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who led the new study.

For example, one previous experiment found that Asians tend to dart their eyes around a photograph, while North Americans fix on specific people.

To see if religious differences might skew perception, Hommel’s team tested 40 Dutch atheist and Calvinist university students, who, religion aside, had similar cultural backgrounds.

On a computer screen, Hommel’s team showed participants a large triangle or square made of either smaller triangles or squares. The volunteers had to focus on either the big object or its component shapes, and indicate whether they were square or triangular.

Both groups recognised the large shapes more quickly than small, embedded ones, but the Calvinists picked out the smaller shapes 30 milliseconds faster than atheists, on average – a small, but significant, difference.

This could reflect a greater focus on self than external distractions for Calvinists, says Hommel.

He suggests it may even be a cognitive consequence of their religion and speculates that Calvinists might be more inward looking than atheists because they have lived their whole lives with an emphasis on minding their own business.

(Image: the word “Ali” on the moon)

People have asked me what I’m giving thanks for this year. There are many things, but science is high on the list.

Science on the Web

Back in the bad old days, when we had to walk barefoot to work uphill both ways in the snow, science could be hard to access. If you lived in a city, you might have been lucky enough to have science museums and planetariums to visit, and a large library that carried a good selection of the latest books and journals. Smaller towns weren’t so lucky. To get cutting-edge science news, you had to subscribe to expensive journals, buy expensive books that were out-of-date within a couple of years, and hope like hell that your teevee stations would eventually air something informative.

It’s a little different now. All you need for a world o’ science is a computer and an internet connection.

Here’s just a smattering of some of the awesome science available free on the Web:

USGS Evening Public Lecture Series

Don’t live in Menlo Park, CA, but still want to attend some of the most awesome public lectures available? Look no further! The United States Geological Survey posts its lectures to the toobz, and it’s awesome stuff. They bring science to the public in amazing ways. It’s like having the National Geographic research teams pop into your living room for an evening of Q & A.

TED

Ideas worth spreading indeed! If you’re starving for more lectures after watching the USGS series, TED has some gorgeous talks on evolution by some amazing speakers. You can hear Steven Pinker talk of the blank slate, or Louise Leakey delve into human origins, or David Gallo rhapsodize on the deep oceans, or… just go! You’ll be in great company – Dawkins and Dennet have talks up, too!

NASA’s JPL Solar System Simulator

Encyclopedia of Life

This ain’t the encyclopedia set you grew up with. Not many homes could afford a set comprising of 1.8 million pages – one for each of the known species on Earth. And these pages contain up-to-the-minute information, tons of color pics, and additional resources – all for free.

Need a scientific paper? Can’t afford to pay out the nose? At the Public Library of Science, science is indeed free! All papers are published under an open access license, and delivers high-quality, cutting-edge science right into the public’s hands. This is what science should be – free and ours for the asking.

There’s a World Wide Web of science out there, complete with interactive features, animations, and all sorts of other brilliant ways to bring science straight to you. Go forth, explore, and enjoy!