Supernatural’s second episode, “Wendigo,” introduces the monster-of-the-week theme that defined much of the first season. It also introduces us to the show’s blithe cultural appropriation. One thing you definitely don’t turn to SPN for is their enlightened take on social justice issues. But seeing what they get wrong can show us how to get it right, and tell better stories in the process.

My excellent companion Zeroth has the episode summary and description of the things they got right here. If you haven’t read it, you might want to start there. All up to speed? Awesome. Let’s talk wendigos.

I wish I had two things: a TARDIS and a copy of Shawn Smallman’s Dangerous Spirits: The Windigo in Myth and History. Then I could hoof it back to 2005, wave that book in the writers’ faces, and point out the paragraph when it says they got the fact that wendigos can mimic human voices right, but precious little else. Then, after a bit of a laugh, we could get into a meaty discussion about what the wendigo has meant to European-Americans versus what it means to the indigenous cultures that birthed the myth, both in their past and in their present. And, hopefully, they’d get a far better story out of that discussion. They could have told a story that, rather than using the wendigo as an exotic-to-white-people monster, honors its traditional elements, and foregoes its Euro-American interpretation in favor of indigenous ones. They would told a much more interesting tale.

Let’s first briefly explore the SPN version versus the Algonquian peoples’.

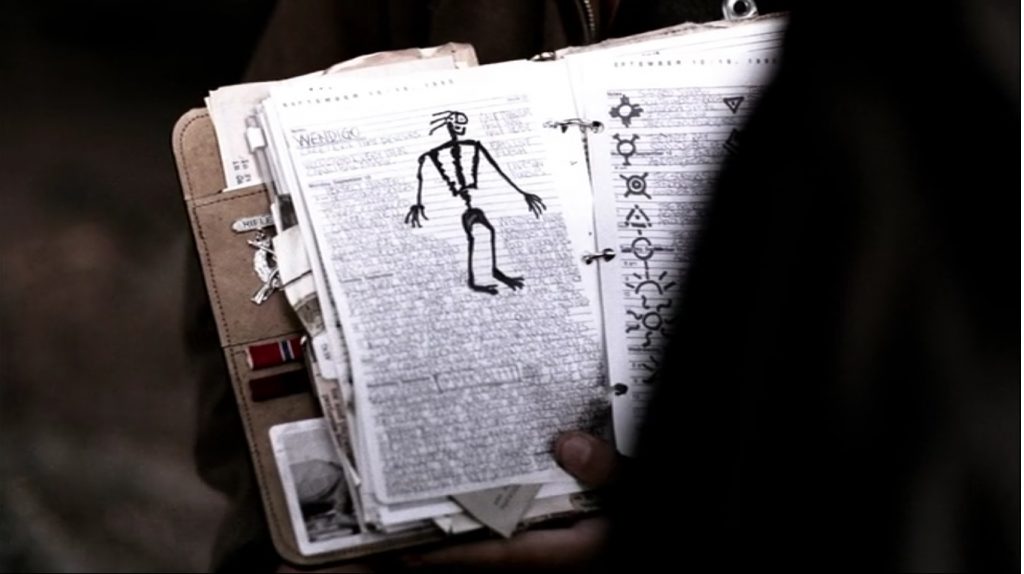

In “Wendigo,” the creatures are, without exception, former people who turned cannibal. It’s strongly implied that they’re almost always male: “Each one was once a man,” Dean says. “Sometimes an Indian, or other times a frontiersman or a miner or hunter.” And the way they transform is “always the same. During some harsh winter a guy finds himself starving, cut off from supplies or help. Becomes a cannibal to survive, eating other members of his tribe or camp.” After consuming enough human flesh, they “become this less than human thing…. always hungry.”

They’re all now hundreds of years old. They hibernate for long periods of time. They come out of hibernation to grab a new batch of humans for meat, some of whom they store alive. They have long claws, are preternaturally fast, and superb hunters. And they can only be killed by being set on fire.

How does that stack up to actual Algonquian traditions? In some respects, quite well. The various Algonquian peoples had varying conceptions of what the wendigo was, but certainly, one way to get a wendigo was to be a human who became a cannibal. But it was more than starvation that could force a person down that path. It happened to some people in dreams, which weren’t considered all that different from the waking world. If a wendigo tricked you into eating human flesh in the dream world, you were screwed in the waking one. You could also become a wendigo if you froze to death, or if a shaman cursed you.

Wendigos weren’t always transformed humans, though. In very ancient tales, they were spirits of winter who transformed the people they touched into monstrous cannibals with hearts of ice. And they wouldn’t stay human sized: as the years passed, they became giants.

And wendigos could be created from anyone, including women and children. Studies of Algonquian myths show the ratios of male to female wendigos to be surprisingly balanced. And grandmothers made especially powerful wendigos. So there’s one definite way the SPN folks could’ve stepped out of the Euro-American mold: their monster could’ve been a woman. And while many narratives have them as solitary, many other (and often older) tales show them in family groups, with family relationships, and even looking to human communities for a husband or wife. What if the missing brother had been persuaded to wed Grandmother Wendigo’s granddaughter, either due to her tricking him into cannibalism in a dream, or in a bid to protect his community?

In fact, in may native stories, “family bonds were essential to overcome the threat posed by the windigo.” This would have been rich territory for a show based on two brothers to mine, but because they neglected the native traditions, they never quite went there, although they did touch on the idea that self-sacrifice and team work was required to defeat the wendigo. But they could have made that resonate much more powerfully with the family bonds.

As for killing wendigos, there were many methods. In the episode, the wendigo takes most of their gear, leaving them with almost nothing left to defend themselves. But the campsite was pretty much in tact. In many legends, kettles were very useful items for defeating a wendigo, so they could’ve made do with some of the camp cookwear. Also, wendigos were terrified of menstruating women. Haley could’ve protected them by announcing her time of the month, rather than the boys using Anasazi symbols – I mean, at least women’s cycles are universal. It would make a lot more sense than symbols used by a Pueblo tribe that never would’ve even heard of such a thing as a wendigo. Then again, with their dismal record of sexist bullshit, maybe it’s best they didn’t know about the menstruation thing…

There were countless other ways to deal with a wendigo, some not even requiring its death. Yes, the human within could be recovered from a wendigo. Sometimes, all it took was sweating out their heart of ice. Imagine how much better a story could’ve been told, if they boys had known they could save rather than kill the monster? And all they needed was a bunch of hot rocks, some water, and a sweat lodge they could’ve built easily out of materials at hand.

But perhaps the biggest difference is in what the wendigo can represent.

In Euro-American traditions, the wendigo has become a symbol of the dangers of the wilderness, and it roughly serves that function in this episode. Go out into the wild without being prepared, and you can end up changed into a terrible entity. But that’s not at all what a wendigo symbolizes in modern native stories:

In contemporary Indigenous traditions, the windigo has become associated with the danger of greed, capitalism, and Western excess, while in European and Canadian imagery, it is the symbol of evil, wilderness, and madness….

In Euro-Canadian novels and films, the windigo is largely separate from Aboriginal culture, in that there is little meaningful discussion of Native beliefs. Instead, Aboriginal peoples are often associated with a simplified version of the past, in which discussions of colonialism are avoided. In contrast, Native works focus on the traumas associated with colonialism, such as residential schools, sexual abuse, and cultural loss, which are equated with the windigo spirit. Indigenous books, plays, and films draw on a vision of the windigo articulated by Ojibwa scholar Basil Johnston, who described it as being the spirit of selfishness, as epitomized by the Euro-Canadian culture of extraction and environmental destruction: ‘These new weendigoes are no different from their forebears. In fact, they are even more omnivorous than their old ancestors. The only difference is that the modern Weendigoes wear elegant clothes and comport themselves with an air of cultured and dignified respectability.’

So, that probably wouldn’t work quite right for a monster-of-the-week – but there’s no reason why the wendigo in this story couldn’t have taken some of the native symbolism on board. Instead of a starving frontiersman, the wendigo Sam and Dean encountered could have been revealed as a miner so greedy to exploit the riches of the mineral vein he and his partners were working that he devoured those partners to keep all the profits for himself. And, perhaps, the only way to kill the monster he’d become was by using a stick of the very same copper he’d killed for. Even though the boys need to be the heroes this early on in the show, their victory could have been due to the native lore their dad had learned and recorded in his journal, thus giving the ultimate victory to the indigenous people rather than all to the white dudes who rode to the rescue in a Chevy Impala.

I could go on for days, but I think you all get the idea. This is why cultural appropriation is not only a shitty thing to do, but ultimately cheats the appropriator as well as the people they’re appropriating from. There are better ways to go about this. If you want a native monster, fine – but honor the cultures those monsters come from. Take the time to do the research and get them right. Acknowledge and honor the people you’re borrowing those stories from. Read and watch the stories and movies indigenous people have used things like the wendigo to tell. Those works aren’t that hard to find. And, while telling your own wendigo story, you can refer back to them, thus both thanking them and exposing them to an audience that otherwise never would have known they existed.

And get the fucking etymology right, while you’re at it.

Here’s a small sampling of films and novels based on the wendigo myth by indigenous creators. If you’re going to tell your own wendigo story, or even if you just want to learn a bit more, check these out first:

Antonia Bird: Ravenous

Joseph Boyden: Three Day Road

Edmund Metatawabin: Hanaway

Tomson Highway: Kiss of the Fur Queen

There’s a definite difference between honoring a culture and appropriating it. Unfortunately, in the case of “Wendigo,” the SPN folks went all appropriation without any honoring. They can do better. We all can do better. And every single one of us who tells stories should put in the hard work to get it right.