[Content note: online harassment]

Usually when we tell people not to do bad things, such as threatening feminist writers with rape or telling them to kill themselves, we emphasize that these things are bad to do because they’re bad to do, not because of who we’re doing them to. You shouldn’t threaten me with rape for writing this blog post because threatening people with rape is a monstrous thing to do, not because I am right and my blog post is correct. Even if my blog post were completely wrong and even if I was kind of a crappy person, threatening me with rape would still be wrong.

But of course, because human beings are human beings, these principles often fly right out the window when we’re angry, frustrated, disempowered, or simply annoyed. Yeah, sure, verbally abusing people online and violating their privacy is generally wrong, but this person is really bad. This person’s ideas are wrong and they need to stop saying them. This person hurt someone I care about, so they deserve this. This isn’t even a real privacy violation, because that information was out there anyway. It’s not abusive to say something that’s just true. It’s not like there’s anything else I can do in this situation. I was really angry so you can’t really blame me for doing this.

Spend enough time among humans in groups–so, maybe a few hours or days–and pay attention, and you’ll notice enough of these rhetorical devices to make your head spin. One recent one that has my brain hurting concerns Amy Pascal, a former Sony chairperson whose emails and other private info were leaked last fall when hackers stole thousands of documents from Sony, which subsequently ended up on Wikileaks.

Considering that this happened so soon after that ridiculous celebrity nude photo leak last summer, you would think that most people would treat something like this pretty seriously. They didn’t. It turns out that Amy Pascal made racist comments about President Obama in her emails, which I think we can all agree she shouldn’t have done regardless of whether or not she had any idea it could ever be public.

However, that someone has done a bad thing doesn’t then make it okay to do bad things to them in retribution. Certain consequences are, I think, appropriate, depending on what the bad thing was. Sometimes people lose their jobs for saying racist things, which (unlike many people) I think is okay. In a multicultural society and workforce, saying racist things makes you a worse employee than someone who is otherwise just like you but does not say racist things. A company that allows employees who say racist things to continue working there is going to eventually alienate a substantial portion of its customers or clients, and so it is in that company’s best interest to fire employees who say racist things.

Likewise, sometimes people lose friends when they say racist things. I think that’s also appropriate. Everyone deserves to decide for themselves who they do and do not want to be friends with. If I don’t want to be friends with people who say racist things, and you say racist things, then I will stop being your friend. Not only am I personally angered and irritated by racism, but I can’t be friends with someone that I can’t trust not to mistreat my friends of color. (And yes, making “racially charged comments,” as they’re known, is mistreatment.)

But is it okay to publish someone’s personal information because they’ve said a racist thing? Is it okay to shame them in a sexist way? Is it okay to specifically go out of your way to publicly embarrass them about something that has literally nothing to do with the racist things they said?

I don’t think so.

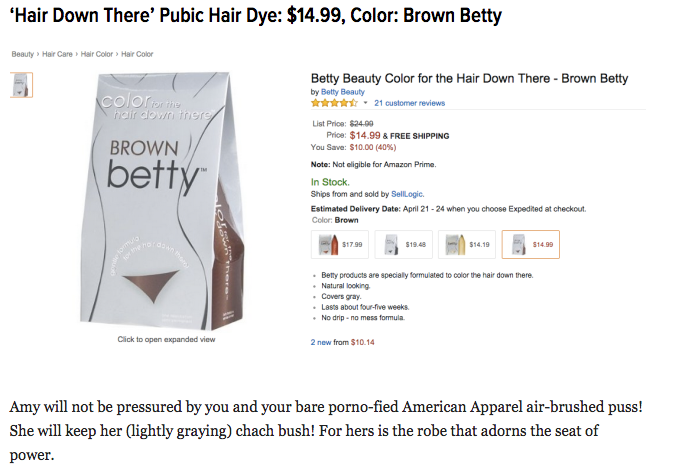

But that’s exactly what Jezebel did to Amy Pascal when they published her leaked Amazon purchases along with “snarky” commentary, shaming her for the personal care/hygiene products she chose to use.

I think we can all agree that this doesn’t add to the conversation. It doesn’t undo any harm done by Pascal’s racist comments or teach anyone why they were wrong. It doesn’t hold her accountable for them in any way. It doesn’t accomplish anything. It reminds me of a bunch of middle school girls publicly shaming and bullying another girl because they found tampons in her locker or because they found out that she bleaches the hair on her upper lip. It’s completely pointlessly cruel and Pascal did nothing to deserve it.

The problem with this genre of commentary is that it celebrates a gut-level delight in the same sort of invasion of privacy that drove Redditors to distribute those nude celebrity photos: Exposing people’s secrets — especially powerful people’s secrets — doesn’t just make us feel good, it makes us feel powerful. And though the Sony leaks show Pascal made hundreds of Amazon orders, the highlighted products seemed picked exclusively to humiliate a woman for attempting to stay young in an industry that demands it. Surely writing about Scott Rudin ordering a bottle of Rogaine wouldn’t have packed the same punch. This doesn’t mean women can’t and shouldn’t critique other women. But humiliating a woman based on her body — whether it’s the private photos she took or the products she ordered — seems like overkill.

In a piece about doxxing “for good,” Ijeoma Oluo has a similar take on this analogous issue:

Freedom of speech also comes with accountability for that speech — but doxxing isn’t about accountability, it’s about silencing. Techniques designed to intimidate people out of the public sphere are wrong, no matter who is doing it. Deciding that we will not stoop to their level and that we will not risk innocent people does not fix racism, sexism, homophobia and the like, but it helps us protect the ideals that we are fighting for.

[…] Harassment and threats must be recognized as the crimes they are, whether they come from MRAs or from overzealous anti-racists. You’ve got to be vigilant in condemning harassment, just as you should if you witness it in the street. We need to stop making excuses for people who get joy from instilling fear in others.

The connection between these two things might not be readily apparent. Should we really compare leaking someone’s beauty regimen with threatening them with violence or doxxing their address? I would argue that we should. Both of these things get justified with claims that the target is such a bad person that they deserve this treatment. But of course, as Oluo points out, innocent people get hit with the splash damage all the time.

I think the problem goes beyond that. If we make a rule that says, “Doxxing/abuse/harassment/threats/shaming is okay when the target did something really bad,” then everyone gets to interpret “really bad” for themselves, and you may not like that interpretation. For instance, there are people online who earnestly believe that I am a threat to their livelihood and to the continued functioning of our society. Many MRAs also believe that feminists pose a serious and imminent threat to their physical safety. Surely by their standards I have done plenty of “really bad” things, such as writing widely read articles about feminism.

I cannot overstate the importance of pointing out that they really believe this. They’re not just saying it to get some sort of Points online. They’re not lying. (At least, not all of them.) They believe this as truly and completely as I believe that inequality exists and must be fixed, that there is no god, that I love my friends and family.

Think about your strongest convictions and how real, how powerful your belief in them is. Now, imagine that someone believes with an equal conviction that I am (or you are) a terrible person who poses a threat to them and to everything they love and care about. Imagine that we have all spent years cheerfully promoting the idea that “Doxxing/abuse/harassment/threats/shaming is okay when the target did something really bad.”

Now try to reason this person out of threatening me or you with death or worse. Try to convince them that if they obtain access to our silly Amazon purchases or private emails, they shouldn’t post them online. Try to convince them that if they have information that could destroy our lives if made public, they should keep it to themselves.

This is why I don’t feel safe in online spaces that promote doxxing, abuse, harassment, threats, or shaming against anyone, no matter how much I fucking despise the person they’re doing it to.

If doxxing/etc is ever okay, then it is always okay. Because if it is ever okay, then we will find ways to justify it in any situation we want. We will always be able to point to someone’s racist emails or tweets. We will always be able to show that they really really hurt someone we care about. We will always be able to claim that the internet would be better off if this person just disappeared from it.

I don’t know what to do about doxxing, quite honestly. I don’t. Sometimes doxxing is the last resort of people who are themselves extremely unsafe and have no idea what else to do. Sometimes doxxing happens because the authorities and the websites where abuse takes place continually refuse to take these issues seriously and address them and help keep people from having their lives wrecked. Why the fuck did it have to take doxxing to stop someone from posting “creepshots” of underage women on Reddit? This sort of thing makes me want to curl up in bed and just scream “what the fuck” and “I don’t know” over and over. I have no answers about this.

But nobody was in danger because Amy Pascal’s Amazon purchases had not been made public. Whatever brief rush of glee that article’s author and readers experienced as a result does not justify the violation of someone’s privacy. The fact that doxxing and shaming and all of that may, in some fringe cases (I said may) be a necessary evil doesn’t mean we now have license to use it recklessly and constantly.

It is so easy and tempting–and seductive, really–to lash out at someone who’s made you angry or upset. It’s easy, too, to justify it to people who already agree with you by telling them how angry or upset you were. But ethical behavior isn’t just for situations when you’re feeling calm and happy. It’s also for the situations when you’re angry and upset. It’s especially for those situations, because when we are calm and happy, we usually need little encouragement to do the right thing.

It is true that taking the high road doesn’t necessarily mean that we “win,” whatever winning even means. It won’t necessarily keep us safe. People will still threaten to rape and kill me because I’m a feminist.

But the more we encourage people to think of this behavior as inherently wrong rather than wrong only in cases where we don’t personally dislike the target or think they did something bad that makes them deserve it, then the more other people will call out this behavior when it happens. The more people call it out, the less socially acceptable it will be. The less socially acceptable it is, the greater the social costs of doing it, which means that the more likely it will be that people who do it will face real consequences, such as getting banned from Twitter or losing their job or losing friends.

And the more people face real consequences for doing these things, the less these things will happen. Not only to the people you hate, but also to the people you love.