In a little under two hours, my friend Andrew Tripp and his student group, the DePaul Alliance for Free Thought, is hosting a fantastic panel called Real World Atheism: A Panel on Godless Activism and Cultural Relevancy. I’ll be liveblogging! The panel starts at 7 PM CST.

Some of the panelists should be familiar to you:

So, watch this space. (Unless I fail to get internet, in which case, womp womp.) It should be a really great discussion.

7:06 PM: We’re starting a bit late because Stephanie has not arrived yet. #ruiningeverything

7:18 PM: Stephanie’s still not here, but Andrew’s opening it up to questions. Ian’s introduction is up first! He says not to throw things at him, by which he of course means to throw things at him.

7:20 PM: Ashley’s introducing herself. She is studying Honey Boo Boo and the representation of poor white trash on television. Cool.

7:23 PM: Ian: “Atheism operates like other social justice topics. It intersects like other social justice topics….They are one and the same. They cannot be separated.”

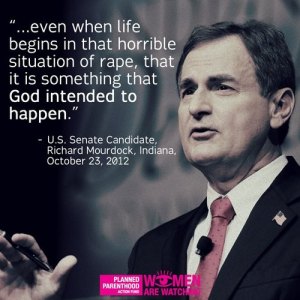

7:25 PM: Sikivu is connecting the anti-abortion movement of the Religious Right with the commodification of Black women’s bodies throughout history; as slaves they were forced to bear children for their masters. Humanism, social justice, racial justice, etc. are all linked.

7:27 PM: Ashley came into atheism from the perspective of other social justice movements, such as women’s and LGBT rights. In LGBT and women’s activism you see that religion is a major factor, so she was initially surprised to see that many atheists didn’t see these issues as going hand-in-hand. “Atheism is necessary to have these discussions…having an awareness of religion and the problems that it brings” is necessary for these movements.

7:30 PM: Anthony is discussing African American humanism and the idea that this life is all you have, so you have to make the most of it–for instance, by doing activism. “We tend to think that atheism and humanism involve an embrace of everything that is modern,” but with African American humanism, you can actually deconstruct atheism and modernism. It’s a way for African Americans to say, “We’re human and we matter.”

Sikivu: There’s a contradiction in that we’re living in a state of first-world exceptionalism, and yet there is still such extreme racial segregation in America in terms of class, neighborhoods, etc.

7:34 PM: An audience member asks Ian about exceptionalism and racial inequality in Canada. Ian on exceptionalism: “America is not exceptional in doing that.” Canada does it too, but America does it bigger!

But there are elements of it that are unique to America. For instance, the KKK made it up to Canada but they basically got “laughed out of the country….Everyone kinda went, ‘Seriously guys, bedsheets?'” The way Americans from the North think of Americans from the South, that’s how Canadians think of Americans. I think everyone in the room just winced.

Ian thinks that’s not quite right, though. Canadian exceptionalism manifests as Canadians thinking of themselves as “the nice ones.” Americans were Mean and Evil and had slavery, and then the Black people escaped and went to Canada and everything was great! That’s what’s taught in schools. But not really though. Evidence: you hear the same awful stereotypes about First Nations people in Canada as you hear about Black people in the U.S. “Canadians are ‘nice,’ but only because nobody’s talking about it.”

7:39 PM: For a while, Canada’s immigration policies were “explicitly racist,” then they were “implicitly racist,” then they were “quasi-racist,” and now, Ian says, people think they’re too liberal and “let’s make them racist-er!”

Ian: “Because Christianity is such an integral part of colonialism…atheists can take it back in a way that non-atheists cannot and say that the founding principles are false.” But until we start listening to those who criticize colonialism and until we learn to look at how atheism fits in, we’ll only be repeating the same problems.

7:41 PM: Stephanie’s finally here, y’all! She’s talking about how we as atheists tend to keep seeing ourselves as “the reasonable ones.” Ashley: many atheists blame everything on religion and think that if it went away, everything would be fine. Blaming the South is wrong, too. Racism doesn’t just happen there. (Although, as a South Carolinian, she admits that, of course, it happens there too.) In some ways, the Enlightenment and the idea of empiricism can contribute to the problems.

7:43 PM: Sikivu points out that this framing of atheism is very narrow. Unbelievers of color see it differently. They know that religion has everything to do with white supremacy, the legacy of slavery, and global capitalism. She mentions that when she was growing up in South L.A. and it was predominantly white, there were almost no storefront churches. Now that it has so many more communities of color, there are many more. Why? Because of de facto segregation in business practices.

7:46 PM: Anthony on the idea that science is the answer to everything: “Science takes place in the context of cultural worlds.” The proof is things like the Tuskegee Experiment, scientists who claim that you can scientifically prove the inferiority of Africans, etc. So, science isn’t enough. If you still believe that atheists could never do this, talk to some people of color.

7:47 PM: Stephanie’s introducing herself belatedly. She’s been associate president of Minnesota Atheists for exactly 8 days now! (Congrats!) Stephanie grew up in Minnesota and Georgia. “In Georgia, everyone looked like me.” Her graduating class had one person of color, who was an adopted Asian man. She says she had a lot to learn in this subject.

7:48 PM: Debbie Goddard is here and she says she’s glad she came! She’s asking about the idea of “scientism” and the idea that African American humanists are poised to deconstruct it–how can people actually do this? How can they help educate the rest of the atheist movement?

7:50 PM: Ashley makes a disclaimer: “I’m obviously not part of the African American atheist movement. [audience laughs] Sorry! Spoilers!” Ian: “I don’t see color.”

She says that the critique of “scientism” is starting to move beyond the African American humanist community, though, even though it can be a tough sell for self-described “skeptics,” who make up a lot of atheists.

Sikivu: Prisoners of color are still being used for scientific experimentation, without consent. So science is continuing to use the bodies of people of color just as it did in the past.

7:54 PM: Ian: “I am a scientist. I science all day long.” He says he is able to deconstruct religion, sexism, racism, etc. by using his scientific training: recognizing where there is likely to be bias, where something might be explained by something else that we’re not seeing, and so on. When someone says that “women are just more nurturing than men,” he says that that’s just one explanation. Could it be something else? Ditto for Asians dominating at school because they’re “super smart,” for instance. So, maybe it’s not that science or skepticism are the problem; maybe it’s that we call something “science” and consider it infallible, and that’s not actually a scientific view.

7:58 PM: Ashley is pointing out, though, that there’s a difference between the process of science itself and the history of the scientific enterprise. Science creates hierarchies about which knowledge “matters,” such as quantitative over qualitative, empiricism over other methods of inquiry. The idea that you should look for alternate explanations and use the scientific method is a good one, but you’re doing it in the context of that hierarchy.

8:00 PM: Stephanie: We might be talking about two types of hierarchies. AHHHHH A;LSDF;ALKSDF.

Ashley: There are valid reasons for those hierarchies, but it means that there are some people and some types of knowledge that “don’t count.”

Ian agrees that we shouldn’t throw out everything that isn’t a randomized control trial. He refers to a survey of women who went to atheist conferences, asking them whether or not they felt safe. There are methodological problems with the survey and it’s not a randomized sample, but it still has useful data as long as we acknowledge the bias. But apparently some YouTube guy disagreed with him and basically said NO EVERYONE’S LYING. Well then.

8:02 PM: Anthony: Most of the invitations he gets to speak are about “diversity in the movement.” But we need to actually change the structure of these organizations. Who’s on the board, for instance, determines what they think is important. Make sure that people you think have the right agenda are holding positions of leadership. “We’re always talking about diversity, but the look of these organizations with respect to leadership doesn’t change.”

8:04 PM: Stephanie: Back to science for a bit. Apparently she’s writing a book. OOOOOO. Anyway. She has a question for the panel: Do those of you who are in leadership positions feel hampered by the constant need to address diversity?

Anthony: What’s important is when other people in leadership positions start talking about diversity, not just us.

8:06 PM: Audience member: Back to science. We idealize it. It’s very elitist; articles are not accessible to everyone, and all we see in the New York Times is “science has found…” Researchers have to compete a lot for funding and are under pressure to publish. So we end up talking about the findings that are “popular,” even if they’re not necessarily the best science.

Sikivu: African American girls are very eager to be involved in science at the middle school level, partially because they’re involved in civic and religious activities where they get a lot of encouragement. But when they get into their classes where they have white/male instructors who don’t perceive them to be as analytical, intelligent as their white male counterparts, it disabuses them of the notion that they can be scientists. And in the media, all you see in terms of scientific achievement are white males. Humanists/nonbelievers of color recognize that it’s not necessarily religion that prevents people of color from exploring science: it’s educational apartheid, institutional racism, etc. in secondary and higher education.

Anthony: This movement needs an appreciation for a diverse range of knowledges, not just science.

8:11 PM: Kate is asking about the fact that STEM education gets so much more attention/funding than other types of education, especially in terms of standardized testing. How does that play in?

Sikivu: Rigorous learning when it comes to science is getting closed out, in part because of Obama’s Race to the Top (or Bottom) initiative. You need college prep classes to get into college, and that’s not necessarily there.

8:12 PM: Debbie is asking about the idea that we need to do social justice work as atheists. When we try to work with others on topics like feminism, etc. because we’re threatening to them and critical. “Part of the atheist identity is, ‘Hi, and I’m an atheist and I think you’re wrong.'” It’s not like, say, a Jew and a Catholic working together, who can apparently bond over their mutual love of god. “How can we get into things like feminist activism and LGBT activism when the idea of being an atheist itself is so offensive?”

Stephanie: part of it is persistence. Minnesota Atheists has worked with the LGBT community for a while, so there’s a relationship. Finding a speaker about abortion rights was more difficult because there wasn’t a relationship like that already. Part of it is the need for destigmatization of atheists.

Ian marched with the BC Humanists in the Pride Parade, which is a really big deal in Vancouver. They carried a huge banner that said, “There’s probably no god so stop worrying and enjoy your life.” The religious groups were all in front of them, though (“There were a whole bunch of Christian groups, cuz they can’t just be Christians!”). He was expecting pushback but Vancouver is one of the most atheistic cities in the country (which is already pretty atheistic), and people were actually cheering out loud. Awww, brings a tear to my eye! But that didn’t happen in a vacuum; it happened after a long process. There were a lot of people who are very involved in the LGBT community and out atheists marching with the BC Humanists. Granted, atheists don’t have the same stigma where he’s from.

Sikivu: Black Skeptics has experience working with the faith community. “That’s been a long, arduous process. We’ve had to meet them on their own terms and on their own turf.” They’ve also been partnering with an LGBT African men’s group to address issues like suicide, homelessness, etc. and develop some sort of mentoring or other resources in the school system. You do have to be able to reach across the aisle and really listen to where people are coming from.

Debbie: “Maybe not using the word atheist sometimes?”

Sikivu: “We use the word atheist!”

Stephanie: Minnesota Atheists obviously does as well.

8:24 PM: Andrew made a face and I’m trying not to burst out laughing, dammit.

An audience member just asked a question about science and culture that took a very long time and I can’t really parse what he’s saying, but let’s see where the discussion goes!

Ian: “Unethical science is bad science. Ethics is part of scientific education, part of scientific process.”

Anthony: People who do unethical science think they’re being ethical…

Sikivu: Who determines ethics?

Audience member: “Without science, society is lost. Without heart, it is doomed. Without science, we are in the dark. But we have to be careful to understand what science means.”

Ian: “Oppression makes empirical sense from some people’s standpoint.” You want something that someone else has, so you’re going to take it. But that’s not a universal value system. Someone made the point that gender oppression creates benefits for men, but actually it doesn’t. You can use scientific inquiry to demonstrate that, and that it benefits everyone–men included, if you eradicate sexism. “Destroying systems of oppression also benefits the oppressor. Only in a very narrow sense does oppression benefit those at the top.”

Audience member disagrees. He doesn’t think oppression hurts the oppressor at all.

8:30 PM: Another audience member: We seem to be separating the hard science from soft science. If you say that we shouldn’t deify hard science, fine. But if you’re saying we shouldn’t deify all science, then you’re ignoring sciences that do take cultural context into account. We should be encouraging people to think scientifically. “We should push back against 73% of people saying Adam and Eve are real.”

Anthony: There has been no deification of the humanities and the social sciences; that’s not the problem.

Sikivu: “You have people waltzing around saying ‘We are all Africans’ without recognizing the offensiveness of that totalizing statement vis-a-vis the conditions of Africans on that continent and here in the United States.”

Ashley: That hierarchy of “some sciences are better than other sciences” is part of the problem. Your question demonstrates that this hierarchy exists.

Audience member: This relates to capitalism. The hard sciences drive profit, so they get the funding/attention.

Stephanie: There’s also the appeal to rationalism. It’s easier to understand physics than biology than sociology. UM I DISAGREE. But she’s got a point. Sciences like sociology are very complex, whereas “hard sciences” are more simple.

Ian: It’s easy to refute religious claims with “Fossils!” “But to understand how ‘Fossils!’ is part of a larger structural system that is subsumed within Christiano-capitalist histories…that takes a lot of work.” Ian cribs stuff other people wrote about capitalism (like Sikivu and Anthony!) because he just doesn’t have time to read all of that. There are purists out there who say “we can’t have these conversations” and who think that we can only talk about atheism, not social justice. “But until they clamp something over my mouth—well, over my fingers, because I blog–until they clamp oven mitts over my hands,” he’s going to keep talking about what he wants to talk about.

You have to use different methods for different questions.

8:38 PM: Stephanie: changing the topic a bit. Do we value people with social intelligence and leadership skills, or do we value the people who are able to stand up in front of the room and talk for an hour?

Ashley: There are definitely organizations who look towards those social things, but individuals in the movement are probably less drawn to that than people who are looking for leaders for an organization.

Stephanie: “If we want to act in the real world, is this something we need to value?”

Ian: Different situations require different skills. In some organizations there’s a huge turnover of leaders because people have different skills, and the needs of the organization change. He doesn’t think this is an answerable question.

Ashley: The Secular Student Alliance does a good job at this, at putting people in roles where they have to learn skills. (YAY!)

8:42 PM: Debbie: “I’m sorry. I have so many questions though!” It seems that at atheist/skeptic conferences, a lot of the people on stage were often scientists/researchers, not organizers/educators/activists, which may be why there was little diversity. But now there’s more of the latter group, and they are more tuned into what’s going on with the grassroots. Blogging helps. Wait, what was the actual question.

8:50 PM: Audience member: There isn’t just one atheist movement, but if there is one, what is the main goal?

Ian: “I would draw an analogy between the atheist movement and the Black community. What is the Black community? There is and there isn’t one.”

Audience: You didn’t answer the question.

Ian: I’ll let someone else answer the question.

Ashley: equality for nonbelievers, and critique of religion as an institution. The goal of critiquing religion fails if you’re unwilling to recognize all of these other things (social justice).

8:52 PM: Audience member: Is there a concern among atheists that instead of deifying a god, people will deify government, think that someone’s smarter than them and should make choices for them?

Ashley: “I don’t think any atheist thinks anyone’s smarter than them.”

8:53 PM: Stephanie: What common missteps do people make regarding social justice issues? For instance, telling you some fact they learned during Black History Month that shows they have no idea what’s going on?

Sikivu: People think that African Americans are so religious because they’re not educated or because of “failure to be enlightened by the science god,” and that’s something to push back against. So is the idea that science is going to be the “silver bullet” against Black religiosity.

Ashley: People wonder “How do I make people want to be a part of what I’m doing?” not “How do I reach out and do something for them?” Ian: “with them.”

Ian: “One thing I really despise is laissez-faire anti-racism.” The idea that if we just stop treating people like they’re different, then we’ll all just be equal! Yay! It’s not a liberal vs. conservative thing. The problem is that racism requires more attention, not less. You have to actually understand how it works. “Whenever someone says race doesn’t matter or race isn’t important, I immediately know they have no idea what they’re talking about.”

Anthony: One problem is the idea that what will produce the society we want is the complete eradication of religion. Rather, we should ask, “what can we do to lessen the impact of religion?” What can we do to prevent the most tragic consequences of it?

Stephanie: We have five minutes left, is there anything anyone wants to leave us with?

Ian: Everyone should read my blog.

Ashley: No, everyone should read my blog.

Ian: After you read my blog.

Stephanie: They’re all really close to each other.

Read all the FreethoughtBlogs!

AND IT’S A WRAP. Thanks, everyone! What an awesomesauce panel.